Are Networks Democratic?

Matt Prewitt

February 9, 2021

The basic point

This essay tries to make a basic point about democracy. It is not a new insight. But I am surely not alone in finding it hard to disentangle from similar and adjacent ideas.

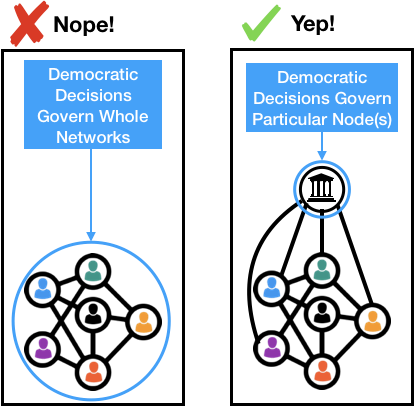

Stated abstractly, the point is this: Democracy by definition does not govern whole “networks” – at least, not directly. Instead, it governs points of authority, which we might call “nodes”. When we fail to keep this in mind, we risk confusing ourselves with talk of “democratic networks.”

A little more explanation

I am using very general definitions:

- A network is any set of identifiable things that affect each other, such as by communicating, trading, or interacting.

- A node is one of those identifiable things. Imagine a nation-state, with all the people and institutions that comprise it, as a big network of interrelated nodes. The government is a node. The people are nodes. Companies and assets are nodes.

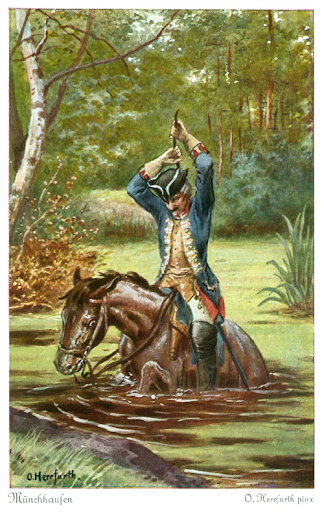

Clearly, democracy is something happening within this network, not outside it. So the notion of that whole network being governed by democracy, or being somehow inherently democratic, appears nonsensical. It is like imagining Baron Münchhausen lifting himself up by his hair.

Indeed, democracy does not govern networks. Nor does it ever fully characterize them. Instead, it governs nodes within them, such as governments. These governed sites of power then influence the rest of the network.

If we think of nation-states as networks, the government simply occupies a position different from all other nodes. It has a special role, whose features include a monopoly on legitimate use of force, and direct relationships with most of the other nodes (such as people and institutions) in the country. But in the end, it is also just another actor in the society.

What about non-state democracy, as in workplaces, tribes, and the Eurovision Song Contest? There too, democracy governs only particular nodes, not whole networks as such. When we say “this country / workplace / song contest is democratic”, what we really mean is that one or several special nodes in the network take direction from democratic processes. The government swears in a new legislator when she wins an election. The office manager purchases a new coffee machine when a monthly vote indicates that this is desired. The producer of the show announces a song contest winner based on delegate votes. Actors with networks – but never complete networks – follow democracy’s orders.

You might be thinking that this is obvious. But like the glasses on the bridge of your nose, it is also easy to forget. For example, people forget this when they assume that increasing access to a system means democratizing it. This confusion has plagued thinking about the global economy, the internet, and much else, for decades. It might be a wonderful idea to help the global poor get access to banking; but that is not democratizing banking. It might be a good idea to get more information to more people more cheaply; but that is not democratizing information. It might be good to connect an isolated, autocratic country to networks of global capital. But that won’t “democratize” it! Just think of all the United States foreign policy that has been wasted on this last confusion.[1]

Because democracy is so powerful and attractive, lots of people want to use it as a buzzword. But the word and the idea are too important to let that happen. Democracy is a structure of power relations in networks that, like a souffle, does not arise automatically. The mixture of plural influences, mutual concern between the participants, has to be just right. So “democratize” should never be used as a mere synonym for “increase access to”, “lower cost of”, or “make more networked”.

Networks are not inherently democratic things. (Nor are they inherently autocratic – both are category errors.) By default, they simply speak the language of power, instead of giving many nodes (i.e., people) equal weight in the way that democracy requires.

Networks can constrain democracy

Consider a strong autarkic government. With big guns and a tall border fence, it can do more or less as it pleases inside its borders. This lets it dictate the terms on which most other kinds of power flow in the domestic network (of which it is a part). For example, through its laws and regulations, it says who owns what assets, and on what conditions.

If such a government embraces the authority of democracy, then democracy really occupies that society’s driver’s seat. This is perhaps the closest thing we might imagine to the abstract idea of a “whole (socio-political) network governed by democracy”. But it is not all the way there. The democratic government is still part of the network, and thus subject to inevitable non-democratic influences (such as when officials are bribed). Further, the near-complete authority of democracy here depends on two related things that never exist absolutely: a monopoly on coercion, and isolation from other networks.

Do not mistake this for an all-things-considered argument for autarky. I do not believe in autarky. I only believe that, as a thought experiment, autarky illuminates something about democracy and networks.

- A monopoly on coercion

For any one node to approach control of the entire network in which it is embedded, it needs to monopolize the highest layer of power in that network. By “highest layer,” I mean simply that some forms of power tend to trump others. Coercion is a higher layer of power than economics, because whoever controls it says who owns what.[2] Economic power, in turn, sits higher than the cultural power you can get solely by wearing expensive clothes, because it buys expensive clothes.

These forms of power loop back upon one another, of course.[3] But it is still useful to understand which layers tend to dominate which others.

- Isolation from other networks

In an autarky, the absence of relationships with external networks lets democracy hold greater sway. To see why, imagine it ceases to be an autarky by inviting outside capital into its borders. Foreign governments will then expect something in exchange – for example, that domestic capital also be allowed to flow out from the (former) autarky, into their countries.

Even though the former autarkic government still has the biggest domestic guns, and is still democratic, this change breaks its monopoly on coercion. The society’s newfound embeddedness in wider networks constrains democracy’s power to maneuver society via the government.[4]

When a small network links up with a bigger one, this attenuates the ability of any node within the small one – including democratic governments – to determine the network’s overall character. As societies grow more dependent on outside powers, the consequences of their internal democratic decisions grow more unpredictable.

Why we keep mistaking networks for democracies

If networks can constrain democracy, why do we keep mistaking them for an automatically pro-democratic force? Because they constrain autocracy the same way. Assuming that the enemy of democracy’s enemy is democracy’s friend, we fall for a logical fallacy. Networks simply act as a general solvent upon fixed authority structures.

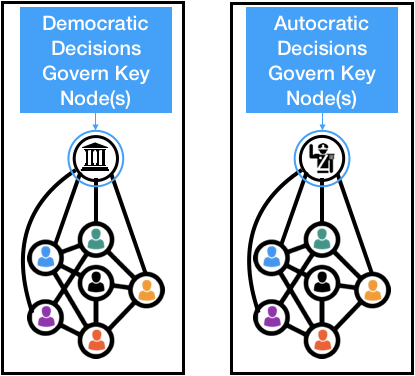

Autocracy, just like democracy, is only a mode of authority over nodes. Both forms of governance merely describe structures within networks – the way that certain nodes, such as governments, take direction from other nodes, such as citizens or officials.

So when we notice networks constraining autocrats, although we might rightly celebrate it, we shouldn’t mistake it for democracy. It’s a little embarrassing how often this has confused us.

The power networks understand

I mentioned that power is networks’ only native language. What kind of power? Any kind. Whatever the nodes react to.

In networks of people, coercion tends to be a very powerful currency. People don’t want to get hurt. But coercion isn’t the only thing people understand, of course. Let’s return to the idea of distinct, yet interconnected “layers” of power influencing one another.

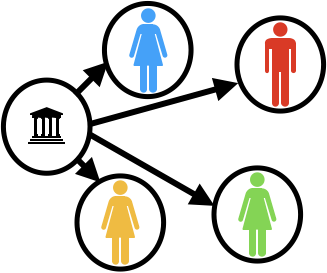

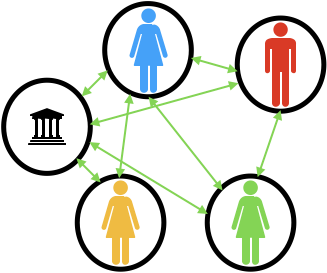

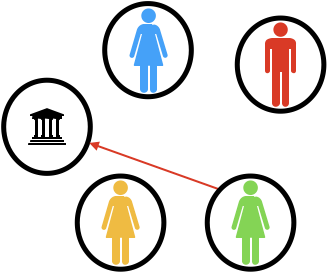

In a typical state, we might have a top layer that looks as below. The arrows from the state to the people indicate that the state can physically coerce people, while people cannot coerce the state. Notice, too, that the people cannot coerce each other:

I should note that coercion need not work in this “centralized” way. I only depict it this way because it is simple, and it corresponds loosely to the way states work. But coercive layers can of course have multiple coercive actors (indeed at a high enough resolution, all do).

Beneath that layer, we might have another layer with the same actors, where people and institutions influence each other with money:

This layer looks different. Unlike on the coercion layer, no party has a monopoly on power here. Most parties can influence most other ones with money, though of course their arrows will have different “weights”.

Then there might be another layer depicting who controls the government. An autocracy might look like this, indicating that one person is the dictator:

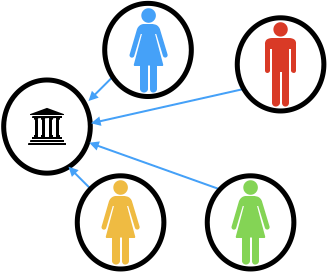

While a democracy might look like this:

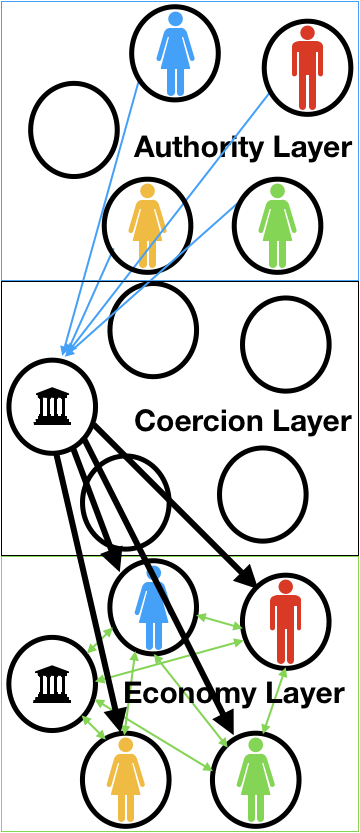

I find it useful to imagine these layers stacked upon each other, with each node “appearing” only on the levels where it is actually exerting power; and the arrows running not only within layers, but across them, indicating their interconnections:

Even better, instead of imagining these hierarchically stacked, you might imagine them arranged in a circle, so that each layer can influence each other one. (I won’t try to draw that.) Also, I’ve only depicted three “layers” but there are many others, such as social and cultural layers. There is a limitless range of possibilities as to how layers interact.

Notice too that our most sacred norms and institutions modulate which nodes are active on each layer, how much “weight” each node has on each layer, and how the arrows flow between the layers. Much of the law consists of building partitions between and within layers to regulate unwanted patterns of influence.

Moreover, when societies build connections to other societies – as in the earlier example of an autarky opening its borders – they embed themselves in larger networks, inviting complex influences from countless additional nodes.

Finally, let’s not forget that networks are never static but always changing. Connections sprout and wither; the weights of the nodes and connections between them fluctuate.

This is a view of society as a multidimensional network.

Coercion and corruption

The pattern depicted above is important to democracy: A coercive layer that can radically restructure other important layers is subordinated to an authoritative layer in which all the relevant participants have equal say. The coercive layer need not be centralized, as I depicted it above – but the authoritative layer must give everyone equal-weighted influence over it.

If the arrows from the coercive layer point back to the authoritative layer, democracy is defective. If arrows from the economic layer point to the authoritative or coercive layers, that also might be a problem – although it’s a bit more complicated. Basically, we should be worried about that insofar as the power on the economic layer is just a slightly-blurred version of the coercive power above it (for example, because the laws uphold unjust property interests like slavery or monopoly); and/or if the economic layer can buy authority from some voters without properly compensating the others whose influence is thereby diminished. These are just formal ways of thinking about what corruption is. I would point again to my older writing on this.

Other examples

In most power structures, democratic or otherwise, it’s possible to talk about authoritative layers, coercive layers, and subordinate socio-economic layers.

On big social media platforms, shareholders comprise the authoritative layer. Below that, power in the coercive layer is highly concentrated in the companies and executives that run the show. They do mostly as the shareholders say. And the socioeconomic layers are the humans and communities transacting on the platforms. Democracy plays little role because the shareholders are not the same people subject to the authority of the coercive layer. The situation resembles privately owned utility monopoly with no accountability to the public.

What if we zoom out and look at the data economy as a whole? Here, things appear messier and less totalitarian – but not more democratic. The authoritative layer is largely defunct, because many parties wield the power to coerce, and yet don’t listen to any authority in particular. (I can share my friends’ data without their approval, and they can all share mine.) The coercive layer is a chaotic wild west. And the socioeconomic layers are just being dragged along for the ride. The data economy is a perfect illustration of how decentralized power doesn’t always give rise to democracy.

Notice, however, that both systems above could in theory be radically restructured by coercive state power, if states so chose. Moreover, collective bargaining entities that controlled data would provide an opportunity for more democracy to arise by constituting new power nodes accountable to democratic authority.

Layers immune to coercion

It’s interesting to think about socioeconomic layers immune to coercion. In fact we don’t need to imagine it. Because blockchain networks cannot be shut down or fundamentally modified without forking, they resemble socioeconomic networks largely immune to the government’s coercive power, and therefore also outside the reach of nation-state democracy.[5]

I think this illustrates why blockchains inspire fear as well as excitement. They are networks that can influence society’s other ordinary layers – economic and cultural – without being subject to either autocratic or democratic coercion.

Networks like this are not going away. They are going to remain a part of the fabric of society. Burying your head about in the sand about their possible implications will not help anyone.

If blockchains are going to have a democratic authority layer, it needs to be built into them at the outset. For while evolving laws and norms can give rise to the democratic authority layers that sit above governments, the fundamental authority in blockchain networks is code that cannot be changed except in exceptional circumstances. Yes, code can be forked, and the networks can be pushed to change by overwhelming hash power. But these levers of power are extremely coarse-grained. Retroactively building democracy into important blockchains might therefore be even harder than establishing democracy in monarchical societies.

How can we build in democratic authority layers? First, blockchain networks must build in proof-of-person layers to make their basic levers of power susceptible to democratic control. Second, just building them is not enough – we need to nurture networks that are structured this way. Blockchain networks with built-in democratic authority layers must outcompete ones without them, if we want democracy to hold sway in the areas of offline life where blockchain networks become influential.

Cats out of bags

Blockchains are not special. If you squint a bit, they aren’t even new, because information has always flowed through fundamentally uncoerceable networks. Once a piece of information is shared by many actors, no coercive layer can “put the cat back in the bag.” Yesterday’s governments couldn’t “unprint” embarrassing news stories with any more ease than today’s governments can shut down blockchain networks.

Good governance has always been about resisting entropy while also allowing people, technology, and networks the freedom to grow, change, and evolve. And democracy, as a special structure within the great power networks of society, has shown itself to help facilitate this. In cases like the French revolution or the post-colonial era, establishing democracy meant fighting for authority over key institutions such as governments – that is, important nodes in power networks. But in other cases, the struggle for democracy has meant competing against external, non-democratic systems, as in the 20th century struggles against fascism and soviet communism. There, democracy had to strap on its shoes, win races, and basically work better than its rivals. It had to prove itself as a more efficient network design.

Today, we should fight both kinds of battles for democracy. We need to reform traditional institutions, such as property and voting, to make them more democratic. But we also need to pay attention to the networks that are being built outside the reach of the government. Fighting for democracy in these new spaces means helping the networks that have democratic authority structures built into them outcompete the ones that don’t.

Conclusion

Networks aren’t democratic. Instead, democracy is a special, dynamic structure inside of networks that gives people shared control over important nodes within them.

The whole history of governance involves regulating the way that different “layers” of power – coercive, economic, cultural, etc. – influence one another. Democracy tends to involve establishing shared control through norms and laws over the most dominant layers of power, usually coercive power.

Today, important networks are emerging that are hard to subordinate to the coercive power that has historically been democracy’s key lever. Yet they have their own internal layers of dominant power that might answer to democratic authority if they were built to do so. We should put a thumb on the scale for the ones architected to accommodate democracy, that they might outcompete the ones architected to preclude it.

Thanks to Divya Siddarth, Glen Weyl, Paul Healy, and Jennifer Morone for helpful comments and conversations.

Notes

The original meaning of democracy is power or rule (kratos), by the people or constituency, (demos). Today it also has a Californian vernacular meaning, along the lines of “opened-up” or “accessible”, as in democratizing culture. I am not denying the currency of that vernacular usage; I am trying to clear up some of the confusion it has caused. ↩︎

Yes, blockchains enable economic power (and other forms of power) to escape coercion, in a way. I’ll get to that. ↩︎

One of my favorite movies is 1979’s Being There, starring Peter Sellers, directed by Hal Ashby, and based on a story by Jerzy Kosinski. In that movie, a white man in his 60s wearing expensive clothes ascends to the pinnacle of state power despite being utterly naive and ignorant, largely because his appearance and bearing permit him to influence other expensively-dressed white men who control government and industry. ↩︎

Here’s why. Imagine that foreign capital flows in to build factories. Then suppose that the people vote for more stringent factory labor conditions. The possible downsides of this vote are worse than they would have been under autarky. To be sure, even under autarky, such a vote might have inspired domestic capital to flow away from manufacturing. But foreign capital is more likely to leave the country entirely, and less likely to adjust to the new rules. The unpredictable ripple effects of capital flight thus encourage voters to refrain from regulating society in the ways that directly reflect their values, and instead to compete with other jurisdictions to be a permissive environment for mobile capital. Under democratic autarky, voters asked themselves a question about values that they could largely answer on introspection. In a non-autarkic democracy, voters must also ask how foreign investors would react, a question that cannot be answered without reference to the circumstances and values of actors outside the society. ↩︎

I realize, of course, that governments can have huge impacts on blockchain networks. But their power over them is more coarse-grained than over almost anything else they might wish to regulate. They can cut off access, or sanction users, but they cannot change the rules that govern existing blockchain networks, because no one can. ↩︎