Between Abundance and Scarcity

Matt Prewitt

April 15, 2020

This dense piece is not an easy read. But it will be of interest to those looking to explore the deeper connections between voting reform and property reform, and the tension at the heart of capitalist democracies.

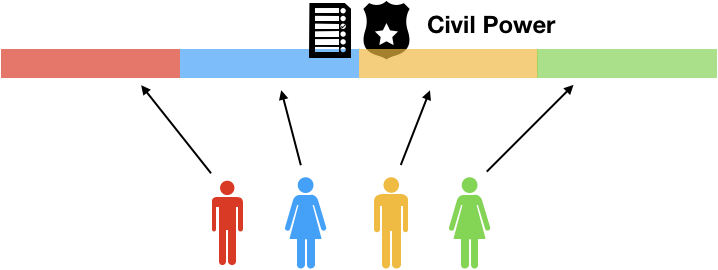

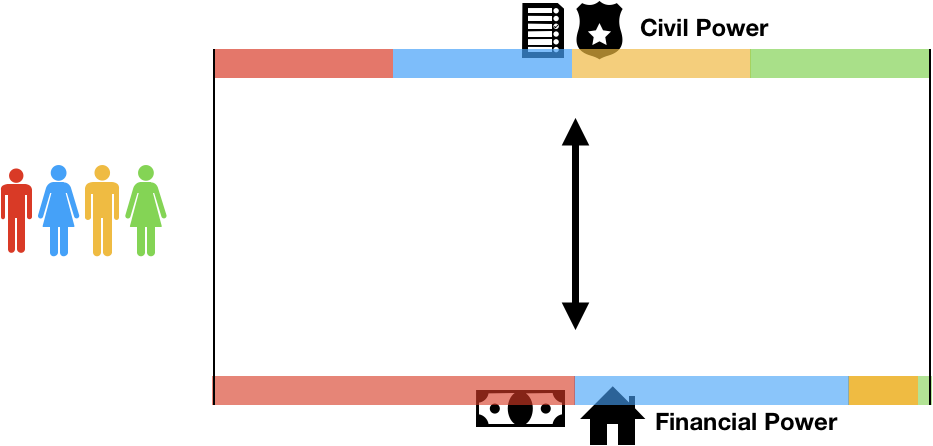

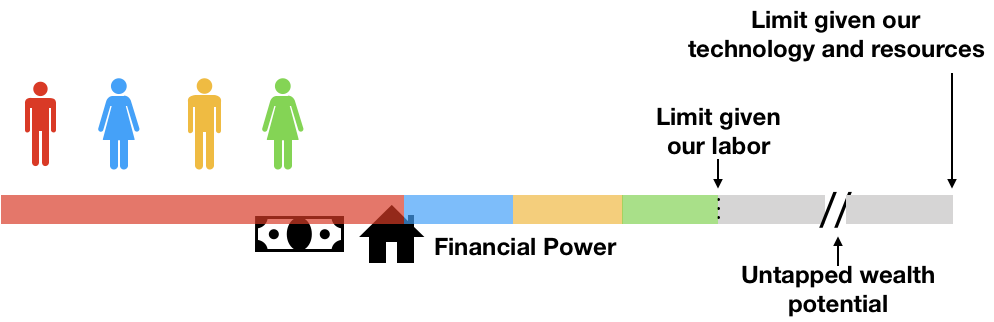

In a democracy, every citizen possesses an equal share of the state’s coercive power. They are thus entitled to equal control over the state’s coercive apparatus through voting:

However, the same citizens possess unequal shares of the society’s total wealth:

Democracies with a capitalist ethos see nothing to worry about in this mismatch. This follows from two widely-accepted premises.

- On the premise that no person’s control over the state can increase without decreasing another person’s → capitalist democracies “lock in” peoples’ civil equality

- On the premise that no person’s increasing wealth makes another person poorer → capitalist democracies let people diverge financially

Unfortunately, both premises are wrong.

Civil power is not a zero sum game

Let’s start with the first premise.

Restated slightly, it asserts that there is a “fixed pie” of control over the state, which can be reallocated but not grown. Here is the error: This assumes that extant authority[1] over the state is fully exercised. It imagines control over the state like water in a glass full to the brim, so that if any is added, some must be subtracted. But in truth, the state is partly out of anyone’s control: With better information, for example, we can increase the degree to which the state is being steered, by anyone.[2] The glass of theoretical authority is never really full.

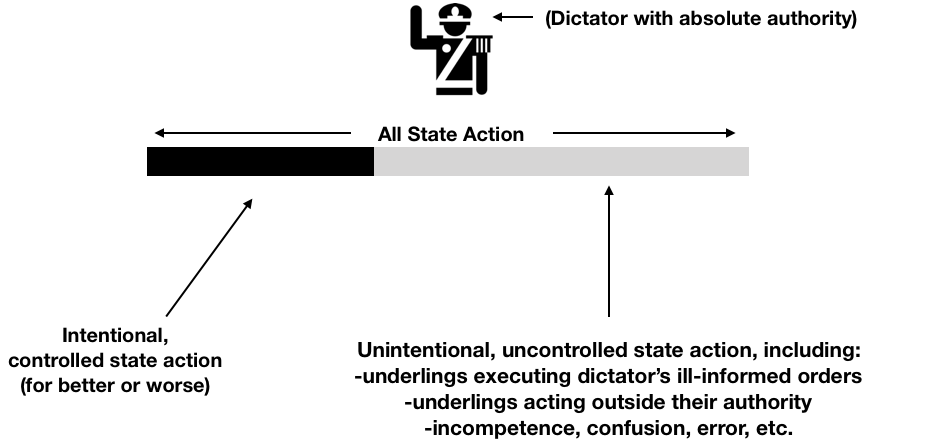

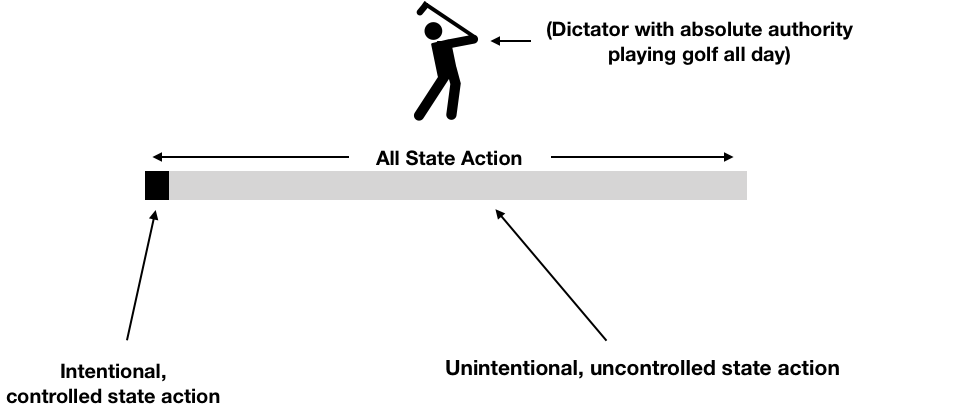

To illustrate, suppose you were an absolute dictator. On paper, you would have 100% control over everything the state does. But now imagine actually trying to exercise that control. No matter how strong your management skills, there would be slippage. You would have to delegate authority to underlings, who would in turn deputize small armies beneath them. You could issue directives, but their accurate execution would depend upon the diligence of agents you couldn’t directly monitor. Even worse, your directives’ quality would depend on flawed information provided to you.

Thus, in spite of your absolute formal authority — and even if your intentions and your management skills were excellent — large amounts of ill-informed, uncontrolled, or otherwise akratic government action would happen on your watch:

[3] Indeed, history is littered with examples of chaotic dictatorships running more or less out of anyone’s control:

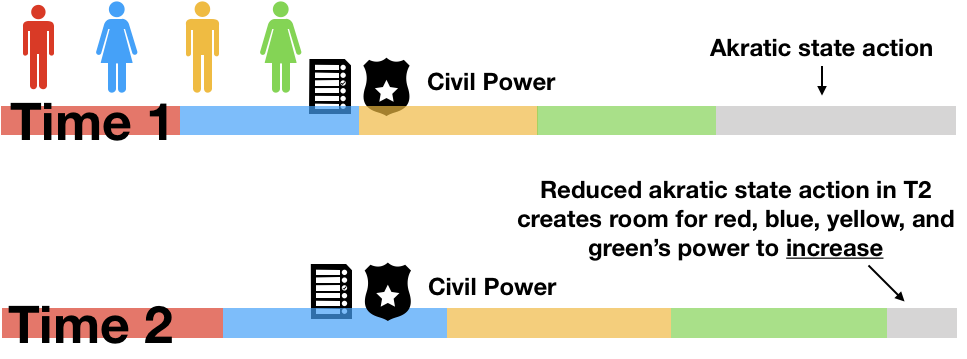

The margin of akratic action thus represents room for growth in the “pie” of civil authority. This is true in either a dictatorship or a democracy. Thus, the control over the state apparatus that we exercise through voting does not draw upon a fixed-sum good.[4]

Full control is impossible

It bears emphasizing that “full control” over the state is always chimerical. Dictators, bureaucrats, and democratic citizens alike can approach it, but never finally seize it. This is a natural consequence of the fact that all humans — dictators, presidents, judges, police officers, and voters — operate with imperfect information.

Interestingly, the fact that akratic state action arises from information processing deficits means that democracies have a built-in advantage. For in a democracy, citizens supply irreplaceable information precisely by steering the state from the ballot box. By contrast, even a benevolent dictator can only guess at what his subjects really know and want, because he has by definition excluded them from governance. Thus, by involving the minds of all their citizens in governance, democracies have the (theoretical, though often unrealized) potential to exercise power far more wisely than autocracies.

Obviously democracy can be terribly dysfunctional and it is imperfect under the best circumstances.[5] Democratic decision processes need a serious overhaul (with quadratic voting, among other things). Ultimately though, I believe democracy can outperform dictatorships not only in terms of legitimacy, but also in terms of decision quality and speed.

But I digress. The main takeaway here is that all states have a problem with akratic action. That means, perhaps surprisingly, that the entire “pie” of civil powers can actually grow, not unlike the economy.[6]

Wealth is not an infinite sum game

The second incorrect premise in capitalist democracies is that one person’s increasing wealth never makes another poorer. I do not want to spill much ink on this well-trodden ground, but I will sketch my argument briefly to show how it mirrors the previous point.

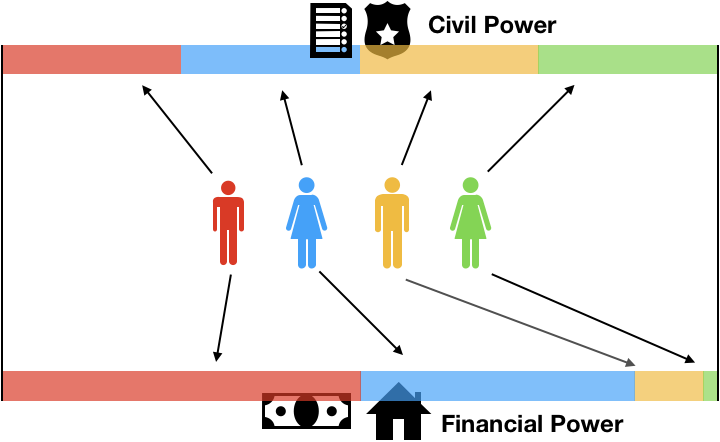

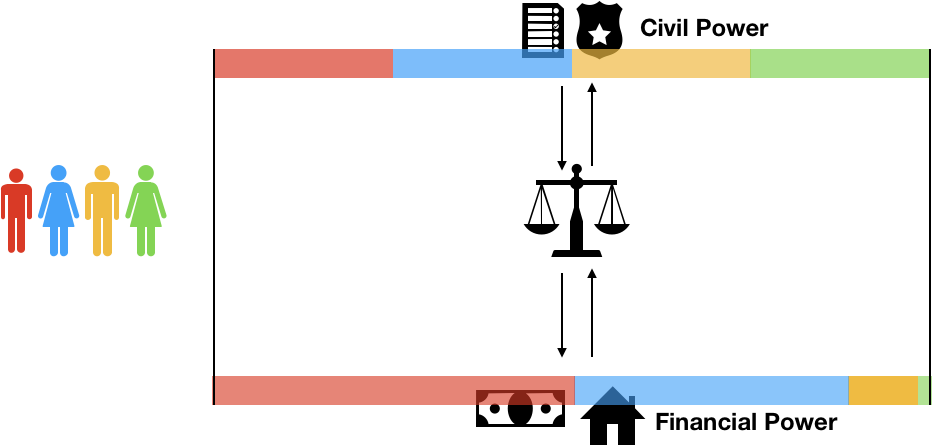

In capitalist democracies, the equal distribution of civil power sits in mutual tension with the unequal distribution of financial power. Like two sides of a battery storing opposite charges, they want to equalize. Namely, rich people want to use their outsize wealth to buy outsize power over the government, and poor people want to exercise their equal civil powers to push their wealth closer to the average level.

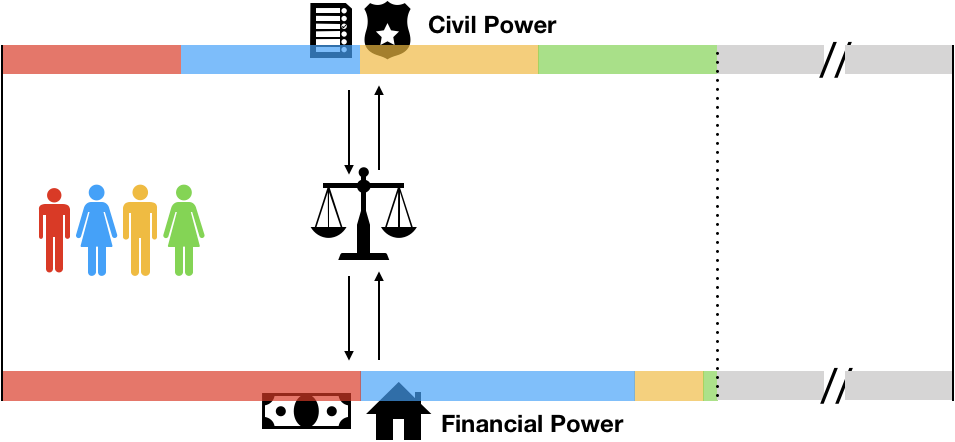

However, again like a battery, there is a partition between these two distributions. We call this partition “legal rights”. Legal rights limit the extent to which each distribution can influence the other:

Loosely, we can speak of two different categories of legal rights: civil rights and property rights. Civil rights preserve our equal civil power. And property rights preserve our unequal financial power. There is another difference. Civil rights are unsellable, or “inalienable,” while property rights can be sold.

We typically think of property rights as giving us power over objects, like land, houses, cars, financial instruments, or works of art. But that view of property rights sees, at best, only one side of the coin. The truth is that when we acquire a legal property right over an object, our relationship with that object doesn’t change, but our relationship with other people does: we become able to call upon armed police to get other people away from the object. So it is a terrible error to think — as many people do — that property rights simply means more wealth, more prosperity, more human domination of inert nature. Property rights clearly give humans power over each other.

It is crucial, at this juncture, to peer into the darkest chapters of history. The colloquial idea of “rights” as a common person’s shield against oppression dates largely to the 18th century, when civil powers were finally extended to people other than hereditary nobility. But if civil rights are a modern invention, property rights are much older. They were already well-established in the dark ages, where they were the incorrigible enemies of human freedom. Indeed, to enslaved people, serfs, landless peasants, and women (that is, almost everyone in the late medieval societies where our laws were forged), property rights were their shackles. They licensed the powerful to use violence against the weak.

Nor did they ever disappear. One might argue that the survival of property rights into the modern era was a sine qua non that made erstwhile feudal lords willing to let the modern era happen.

Modern property laws have sanded the roughest edges of their ugly history, but by no means fully expunged it. For example, property rights today can be transferred to anyone, not just between nobles. And landlords today can do violence to their tenants only via the police and under narrow circumstances (not directly and under broad circumstances, as they once could). But their basic structure never changed. The clearest way of understanding modern property rights, to this day, is as transferable privileges to deploy the state’s coercive apparatus for private ends.

Thus the expansion of the market for property rights was a step forward from terrible feudalism to less-bad modernity. But many property rights — such as to people and land — remained as intact artifacts of an era in which power did not even try to justify itself.

What if this is still true? Many on the political left see something dehumanizing in markets. Could it be that the injustices they see actually have nothing to do with exchange, and everything to do with the property entitlements being exchanged?

The notion of property rights as “nobody’s business but their owner’s” is a romantic fiction. Wealth always depends on society’s willingness to protect it, yet in many cases it licenses extraordinary coercion within the same society. To be sure, property rights sometimes have positive externalities that outweigh their harms — but not always. A true democracy therefore cannot underwrite private property unquestioningly.

Property sound and unsound

In questioning the structure of property, we glimpse the ways that wealth building is not an infinite sum game. In fact, much of what people on the political left find distasteful about “markets” is much more clearly construed as objections to certain kinds of property rights. In other words, the problem is more in the “having” than the “exchanging”.

Yet not all rights to possess, use, build, and enjoy are harmful or objectionable. We must be able to articulate a distinction between productive property rights and oppressive ones.

John Locke, the most important modern property theorist, argued that a property claim was justified only where the claimant “mixed his labor” with the claimed thing, and even then, only insofar as “enough and as good” of the claimed thing was left in the public domain for others to likewise claim. These conditions were wise, and they reveal the defects in many of the property claims in our densely-networked contemporary world. There is not “enough and as good” left to be claimed in the Manhattan land market. When technology companies grab and exploit huge swathes of users’ data, they are staking a claim to something before “mixing their labor” with it — thus undermining not only users, but countless other parties who have legitimate interests in that data. Contractual rights likewise do not stand scrutiny when not formed on a level bargaining plane between people with symmetrical information.

As a shorthand, I call these “unsound” property rights. Wealth accruing from unsound property rights is a private arrogation of state power, and therefore a paramount public problem. It is a co-option of the public police powers into the service of self-interested private parties.

To further illustrate, imagine that a democratic state simply auctioned off its coercive (police and taxation) powers, so that the highest bidder could use them for private profit. Citizens could live under their new investor overlords, or emigrate. Whatever you think of this,[7] such a state is obviously no longer a democracy. And all unsound property rights are shades of that.

In sum, although one person’s wealth can grow without harming anyone else — such as when labor is exchanged for money — this is not always how wealth accrues. Wealth from unsound property rights is a form of coercion — a leakage of public power into private hands. With fewer unsound property rights — for example, if more property rights were based on a system like COST or SALSA — the distribution of wealth would be vastly less unequal.

Putting it all together

When states change over time from being less controlled to more controlled, there is actually room for everyone to simultaneously increase their control over the state:

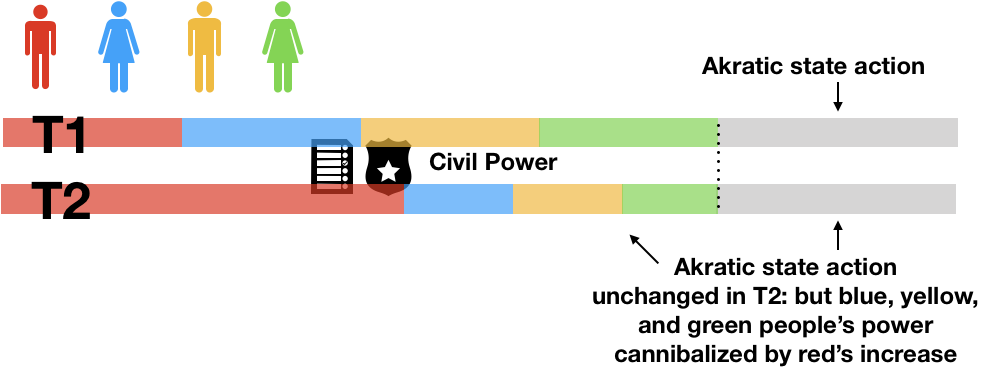

This shows that civil powers are not a zero sum game. Still, obviously, this does not mean we can arbitrarily increase one person’s power and expect it not to cannibalize the power of others:

For the sum total of everyone’s civil power is constrained by the limits of our information and social technology. In other words, the pie only grows when our governance gets smarter. Unless that happens, we cannot give power to Peter without taking it from Paul.

Moreover, there are good reasons to think we get closer to the limits of what’s possible when we involve as many people as possible in power’s exercise, instead of concentrating it in a person, a party, or a handful of oligarchs.

Total wealth can also grow. But it, too, is practically constrained by limits to our labor, technology, and resources.

Because wealth is not a zero sum game, the unusual wealth of some may reflect their unusually valuable contributions to society — such as exceptionally hard work, or exceptional personal contributions to technologies that expanded the pie of total possible wealth. But given that most wealth creation processes are deeply social, there are probable limits to individual wealth concentration in a world of sound property rights. The extraordinary wealth concentrations we see in the world around us are, instead, mostly consequences of “unsound” private property claims — to things like land, natural resources, and data — which derive most of their value not from their owner’s contributions, but from rents on massively distributed network effects. These wealth concentrations stifle human potential by directly excluding people from the power and prosperity they are creating — just like authoritarian governance.

To solve these problems, we must set aside old assumptions about the privateness of wealth, and the finiteness of civil power. We need to think about the sources of “private” wealth as everyone’s business, and we need to think of participatory civil power as something that can grow like the economy.

Civil and financial power in terms of each other

Earlier, I said that civil and financial power are prevented (at least in theory) from influencing each other by legal rights. To recapitulate: civil power may not be used to get other peoples’ wealth because of property rights. And because civil powers are granted at birth and unsellable, wealth may not be used to buy other peoples’ civil power.

But of course in real life, this partition is constantly crossed. Progressive taxes, for example, represent civil power interfering with financial power. Lobbying, campaign donations, and corruption represent the reverse.

But what if, instead of a complicated network of permeable legal rules, we had one simple rule for how to “price” public power in private terms; and vice versa?

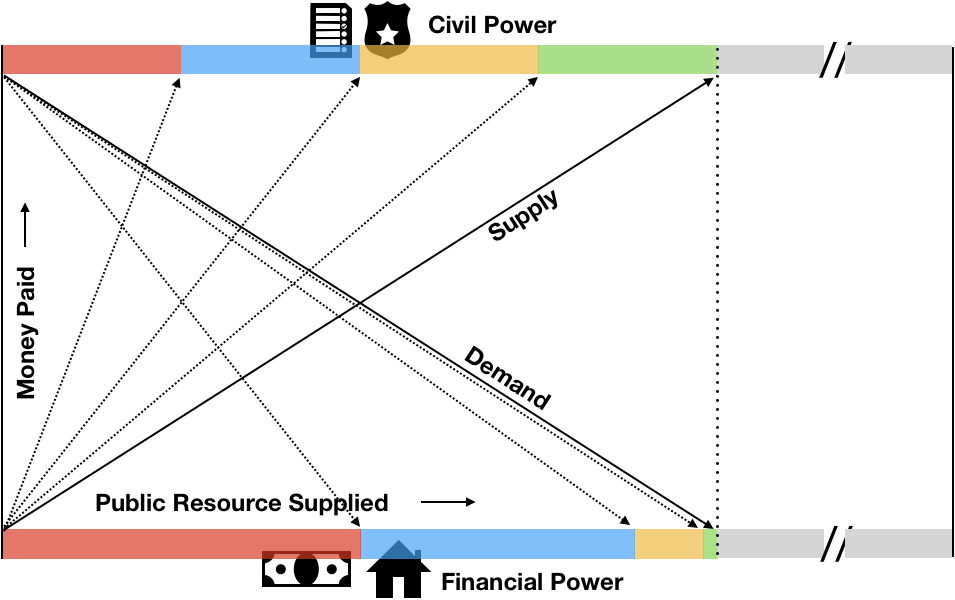

The control that democratic citizens exert over the state aggregates into a “supply curve” for some public resource. These “resources” can arise by commission or omission — for example, building more public infrastructure, or lifting regulations on hazardous activities like polluting.

And private demand from individuals aggregates into a “demand curve” for that public resource. The intersection between the two gives the quantity of the public resource the democratic society is willing to supply.

This, in a sense, is what quadratic voting deals with:

Notice, however, that the desirability of this presumes that all individuals are entitled to the exertions of civil and financial power that generate these supply and demand curves.

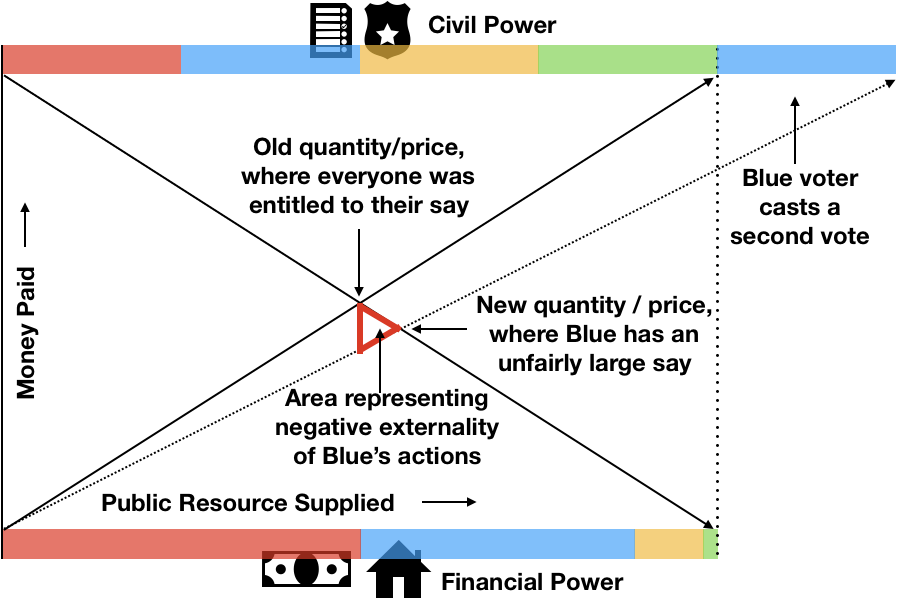

Let us now break that assumption. Suppose something changes based on a unilateral action — for example, someone votes more than once. This moves the equilibrium, changing the amount of the public resource supplied — and therefore imposing a cost on the rest of society.

By casting civil power in terms of financial power, or vice versa, we can see clearly that the structure of that cost is not linear. It is quadratic, because the “deadweight” loss to society is given by the area of triangle, which increases as the square of the individual’s unilateral action:

If the blue voter is willing to pay society for that quadratic externality, however — either in money or in other votes — then why shouldn’t we allow it? Such payment transforms the second vote from an arrogation of power into a fair expression of it.

Quadratic externalities likewise arise when people use their wealth to influence public action.[8] If they “buy” extra political power linearly, as through corruption, lobbying, or simple person-to-person vote-buying, grave injustice is done. But it would make sense to allow people to use their wealth to influence public action if they had to pay the public quadratically— especially if the allocation of wealth itself flowed from “sound” rather than coercive property institutions.

This is all far less shocking when we set aside the antiquated belief that financial power is a matter of exclusively private concern. It isn’t, and never really was. Both ballots and dollars represent claims on the state’s coercive power. It is no coincidence that they are both printed on government paper.

Conclusion

I said that capitalist democracies rest on two premises:

- that no person’s control over the state can increase without decreasing another person’s

- that no person’s increasing wealth makes another person poorer

The first premise is wrong because individual increases in control over the state can flow from a diminution of uncontrolled or akratic state action, rather than a diminution of other peoples’ authority.

The second premise is wrong for two reasons. First, individual increases in wealth do not always grow the pie because they often derive from rent-seeking or unsound property rights. Second, even well-earned wealth is harmful to fellow citizens if it can be used to buy civil power at less-than-quadratic prices.

So let’s be open to more flexible systems! Let’s work to grow civil power as well as economic power; and let’s ask hard questions about where financial power comes from, just as we do about where political power comes from. These are crucial steps toward a radically better political economy.

[1] I am using authority and control to mean different things. Authority means “authorized” control — that is, entitlements to control underwritten by legal or other norms. Control means “exerted” control. For example, if you stay home on election day, you have forfeited your control but not your authority.

[2] Among other things, this means that when Peter gains more control over the state, we cannot deduce that his power was taken from Paul. But this is not to suggest that equality of democratic citizens’ control over state power is not important. It is, and I will return to that. For now it is just important to see that the “size of the pie” can increase.

[3] Dictator icon by Luis Prado of the Noun Project.

[4] The quantity of this good cannot increase to infinity, either. The point is that we need to escape a false dichotomy — with the mental cage of absolute zero-sumness on one side, and the mirage of infinite growability on the other. Both are illusory.

[5] It is also important to recognize that the power voters exercise is coercive. To be sure, democratic decisions may be discursive, reasonable, and civil. But to understand democracy fully one must glimpse its coercive dimension.

Imagine two rival generals standing on opposite ends of a battlefield. Their armies are ready to clash, but the generals are peering through binoculars and counting each other’s troops. The general with the smaller army waives a white flag and the battle ends before it begins. By following this procedure, victory goes to the strongest, yet without bloodshed. Assuming that the soldiers got to choose their army, those generals have just conducted a vote. They have deferred to a majority, not because it is right but because it credibly threatens the other side.

This view of democracy helps explain the historical restriction of voting to white male landowners and other privileged classes: Such people were the only ones with enough coercive power to mutually threaten one another. In voting, they essentially “pantomimed” intra-class violence, averting the need for actual fighting by replicating its results.

Extending the vote beyond the literal wielders of coercive power has constituted moral progress every time it has ever occurred. From noblemen, to non-noble men, to racial and religious minorities, and finally to women — each step has moved us toward a less violent mode of human organization. But greater inclusivity does not change the nature of voting: Even the most inclusive democratic regime still basically imagines each voter as an equal-weighted soldier on a battlefield.

[6] I should address a possible misunderstanding. When I talk about citizens’ civil powers increasing as a whole, you might think that I mean the overall balance of power between states and their citizens shifting in favor of the latter. But that is not what I mean. I am saying that given a fixed quantum of state power, intelligent control over that power can be enhanced. In other words, without reducing state power, it is possible to increase its responsiveness, intentionality, and wisdom. If the civil powers of an entire citizenry were to increase simultaneously in this way, the change in state power would be qualitatively rather than quantitative.

[7] Leaving democracy aside for a moment, notice that the badness of this depends on the escapability of the regime. If it were a small new special economic zone, easy to avoid if you didn’t like its system, it might be fine. But if it were an entire country, it would be abhorrent. And if the whole world were governed under a patchwork of such regimes, poor people would never have a direct say in their own governance. They would simply be running from one exploitive regime to another, with exit as their only form of voice. Their oppression would be complete when private governors realized they could collude in awfulness to avoid competing for residents.

[8] In fact, this is why we customarily have legal rights mediating the implicit market between civil and financial power — that is, why the (civil) entitlements on one side of the partition are “inalienable” and the (financial) entitlements on the other are largely placed beyond the reach of politics by constitutional limits: If we allowed this market to operate without a quadratic pricing rule, so that people could buy civil power with money or vice versa, “deadweight loss” externalities would constantly plague the market. All along, our legal system has simply been intuiting the problem.

*Thanks to Jennifer Morone and Paul Healy for helpful comments.