Three Pathways Towards Decentralized Civics

Calvin Po, Fang-Jui “Fang-Raye” Chang

January 8, 2024

This series of three articles have been made possible through funding from the Ministry of Digital Affairs (moda). Authored by Dark Matter Labs (DML) and supported by the Frontier Foundation, it has been published in collaboration with RadicalxChange, who supported the editing.

With the rise of web3 technology, there is immense potential for imagining new tools for making structural changes in our society in the face of critical challenges like the crises of climate, wealth inequality and democracy itself. In the first part of this series of three blogs, we propose a new framework of ‘decentralized civic infrastructure’ as a web3-native approach for delivering essential capabilities needed for digital participation in society that is resilient and common. In the second part of this series of three blogs, we examine how the government of Taiwan can use its powers to encourage decentralized ways of organizing, if not decentralize its powers altogether.

In this final part, we have sketched out a series of strategic opportunities to develop use cases and pathways for decentralized civic infrastructure. These pathways are still based on the key components of Digital Public Infrastructure: identity, payment, and data exchange, but they explore these components in a broader civic sense, including cultural, media, non-monetary and customary relations. While these spaces have often been considered tangential, we believe they are critical for participation in society. Technology can assist these existing civic practices in building coherence out of the complexity of their communities and bolster their social legitimacy. This is critical especially where the value or need for infrastructure is not currently recognised or addressed by the state.

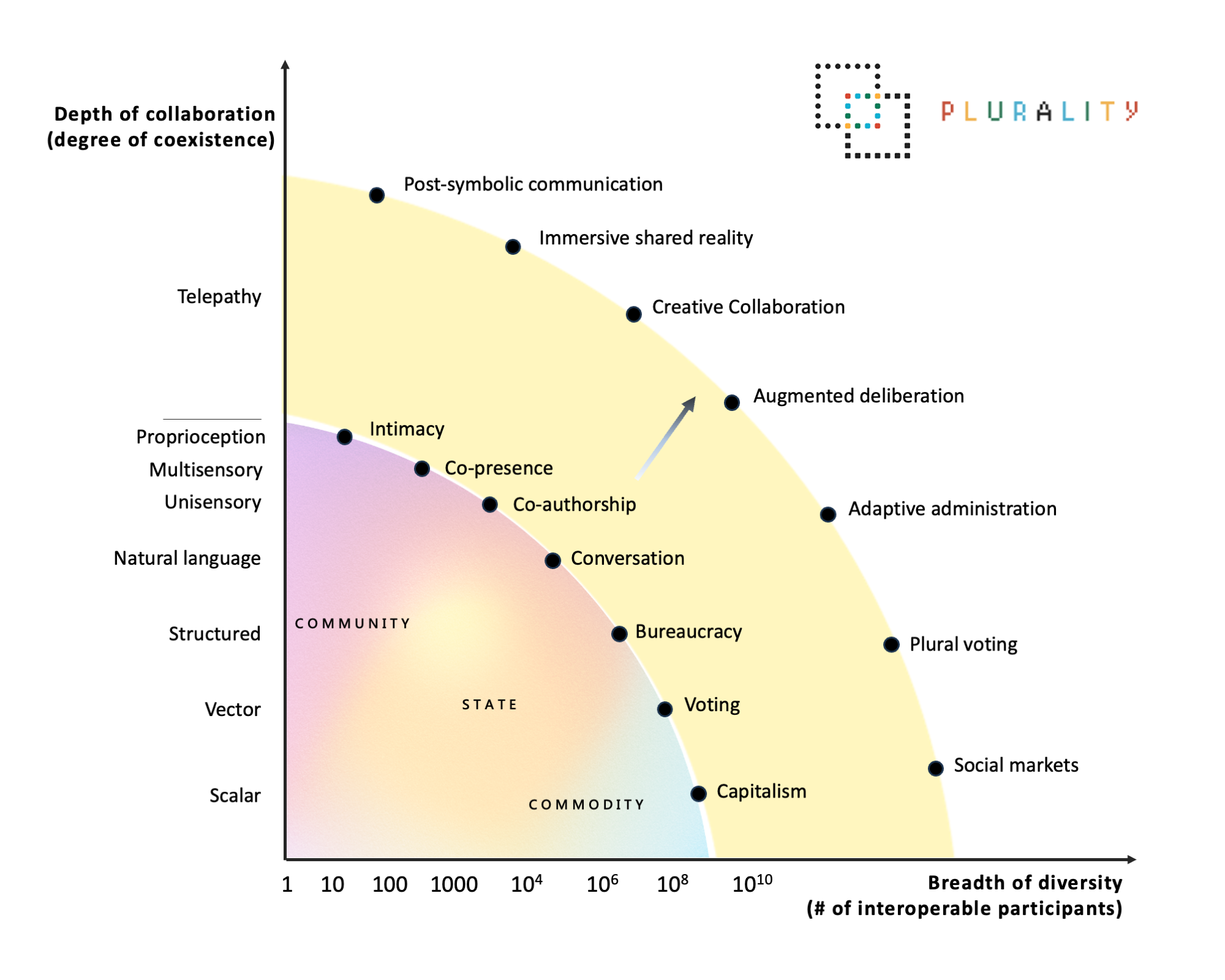

Moving towards deeper collaboration and broader diversity as a pathway towards Plurality.

From Audrey Tang and E. Glen Weyl.

We explicitly describe these use cases also as pathways; they act as strategic entry points that can be evolved in future horizons and shift the wider approach for civics towards ‘plurality’. We use plurality in the sense of deeper “collaboration across diversity”, as defined by Audrey Tang and E. Glen Weyl in “Plurality”, where “collaboration” is “the working of several entities (people or groups) together towards a common goal” and “diversity” represents the range of characteristics and experiences of individuals. We have identified use cases where deeper collaboration and broader diversity, enabled by decentralized civic infrastructure, can have a transformational role in addressing systemic crises we face, by changing how we relate to other humans, and also more-than-humans and ecosystems, and builds up decentralized capabilities to address socially, economically and environmentally critical issues Taiwan faces at the most optimal community level.

Use Case 1: River Relational Identity

This use case centers on the identity system - a cornerstone of civic infrastructure that enables individuals to interact with one another. While centralized systems of identity use data as a single source of truth, decided by one gatekeeping authority, identity as it is actually practiced socially is pluralistic and bottom-up, and emerges from the various relationships individuals form with each other.

We examine the problem of ‘identity’ for more-than-humans: how do we understand and make sense of rivers, which are multi-stakeholder ecosystems? Like humans, their identity is complex and emerges from diverse interrelationships between the river ecosystem’s actors. We propose a decentralized civic infrastructure that collaboratively forms this identity as a way of shaping how citizens make sense of and care for ecosystem actors, and include them in our democratic processes.

Existing practices

Biometrics are often used in connection with identity systems for verifying the uniqueness and ownership of human identities, albeit in a reductive way. Metrics also play a role in how we understand and make sense of more-than humans, including natural ecosystems such as rivers. Taiwan’s Ministry of Environment operates water quality monitoring stations and holds this data centrally on the Environmental Water Quality Information platform. This environmental science relationship with river systems is only a part of the picture. Rivers provide water, food, natural habitat, recreational space, transportation links, and a sense of place, among other things: its identity is not simply geographical, but emerges greater than the sum of the various relationships it has with the communities around the river, human and non-human. To care for ecosystems while recognising these entangled complexities, we need a new system of understanding and interacting with them.

Establishing a River Relational Identity through a Civic Data Trust

Self-sovereign digital identity is based on the principle that subjects should control their own data. What if this were the case for rivers? What if, instead of a centralized Environmental Water Quality Information platform hosted by the government, this duty was transferred to each river, each with its own River Civic Data Trust?

A River Civic Data Trust recognises the relational identity of each river as rooted in the communities around it, with a DAO and decentralized platform for organizing this community. The communities can augment data from water monitoring stations by verifying it with citizen monitoring and contextualizing it with social information (e.g. photographs of suspected pollution events, collective memories and cultural knowledge of places around the river). The Data Trust platform enables collaboration by bringing together the diversity of experience and knowledge of different citizens close to the context to build the shared identity of the river, while reducing the administrative burden on government.

As this identity is based on mutual relationships, this will also include establishing identities of the humans who have relations with the river, including those who participate in the River Civic Data Trust and whether they have specific trusteeship or river monitoring roles. This can be addressed through issuance of decentralized credentials to participating humans based on agreed-upon rules, such as using Soulbound Tokens to be held in their wallets as part of a wider decentralized identity system.

For example, water quality monitoring is currently carried out by trained individuals on behalf of the Ministry of the Environment. In its early stages, ‘water quality monitor’ SBT can continue to be issued by the Ministry to their approved monitors. Decentralized credential issuance offers a pathway towards reducing the central administrative burden: in a few years time, citizens might be able to receive training from a local university on the water quality sampling techniques. Some citizens who have been participating in the River Civic Data Trust for many years might have also established trust within the community. Therefore, the ‘water quality monitor’ SBT could be issued collaboratively by the local university and the River Civic Data Trust, to those who have fulfilled both the criteria of training and trustworthiness. Granting citizens credentialed roles with responsibilities relating to environmental conservation would also make explicit the agency and responsibility of citizens over their natural environment, rather than perpetuating the assumption that such actions are the sole responsibility of government regulators, thus shifting to a civic culture of active citizenship.

Next horizons

The establishment of a River Civic Data Trust implements not only the technical architecture for collaboration, but also supports the building and deepening of the social relationships needed to collectively operate this civic infrastructure for the shared goal of governing the river’s relational identity. Although the initial purpose of the Trust is to manage this through data about the river, this relational infrastructure can be gradually extended for other purposes:

The data could also be used to build interfaces that can elicit care and build up a relationship based on empathy with more-than-human actors. For example, an interface could send people images, sounds, and messages regarding its current state and its needs, based on verified data and information input such as water monitor reports. It could be a story, a call for help, or an invitation.

The Trust can be a basis for building economies of care around the river, issuing ‘care tokens’ to incentivise actions of river stewardship, such as reporting pollution incidents, or removing litter, therefore decentralizing conservation actions to civil society.

Similar to approaches by the rights of nature movement, the Trust can be used to recognise the legal personhood of the river in a process similar to legal recognition of DAOs. This can ultimately allow the river to acquire rights to ‘own itself’, such as acquiring property and land around the river system to be held in trust for conservation purposes.

Use Case 2: P2P Permissioning of Land Use

Almost every citizen has a direct experience of and an opinion on how we use land, starting from our homes and neighborhoods. Currently, the national and local governments in Taiwan have to negotiate these competing individual interests and the common good through their zoning powers, by determining the potential of land as a nationally-critical scarce resource and allocating it to different uses and development plans. Given the complex nature of social, ecological and economic relationships around land, it is difficult for a centralized system to get this right. To get it wrong is damaging not only to the quality of places, but also to the efficacy of Taiwan’s response to the climate crisis.

We propose using web3 systems to decentralize the discovery process of what the land is socially, ecologically and economically capable of, and creating a system in which citizens have direct agency in shaping the future of the environment, and in which conflict between individual stakeholders can be turned into a process of co-creation of their local area through peer-to-peer interaction in an alternative market.

Existing practices

Under Taiwan’s current systems of land use regulation, in which the zoning system is managed primarily by local governments, the state must adjudicate between conflicting interests of stakeholders. This places an exceptional burden on government actors to be able to ascertain accurately the limits of the land, to understand and account for the diverse interests in how it is used, and to allocate this optimally.

While the planning system does include some citizen participation, that participation is limited to advisory exercises, generally employed for large-scale urban redevelopment projects, and citizen input is mediated and interpreted by the government… Especially when this allocation process fails to build social consent, NIMBY activist approaches, such as protests, have sometimes become an alternative way for citizens’ voices to be heard outside of the limited participation in the planning process. There are ambitions for involving more public participation, including statutory requirements in the National Land Use Planning Act to make certain information public and seek citizen participation, but implementation has been limited so far due to systemic barriers.

Peer-to-Peer Permissioning

The maximum use and developability of any piece of land is essentially a scarce resource limited by the ecosystem and the needs and interests of its various neighbors. Land use regulation, at its most basic level, is collectively deciding how to allocate permissions for the scarce resource of ‘development potential’ to balance public and private interests.

This complex problem of reconciling diverse inputs from many individuals for a common goal of shaping the use of land is uniquely suited for decentralized technology. In this proposed peer-to-peer permissioning system, land development rights can be tokenized as Permit Tokens, which each represent a settlement of a negative externality of development: the developer purchases a Permit Token from the affected neighbor, symbolizing an agreement over an externality. These Tokens can be allocated through an alternative market as a mechanism for negotiating conflicting interests, with individual citizens and developers able to actively shape land use decisions directly through signaling their individual preferences through price. Once prices are set, any developer willing to pay that price can choose to purchase the Permit Token based on declared prices without further negotiation. In essence, conflicting negative externalities can be transformed by this alternative market system into co-creating a development plan for the local area through price signals.

In such a system, the tokenomics would be shaped to reflect society’s intended outcomes of land use, such as encouraging environmentally regenerative and social value-creating uses of land, discouraging unsustainable development, and avoiding negative impacts on existing residents. Crucially, structuring decentralized permissioning as a market maintains free choice and avoids centralizing power to decide on land use plans, and instead shapes land use through a collaborative incentive system based on impact. This leaves open possibilities for innovative proposals for land use that achieve the ends of minimizing negative impacts and maximizing positive outcomes, without prejudging the means by which it is achieved.

We propose that this system would require certain elements to work:

LandCoins: Each landowner would be periodically allocated LandCoins minted by the system, which become the medium of exchange. LandCoins can also be additionally generated by regenerative land uses. Rules affecting when and how much LandCoin can be issued might be decided collectively at a system level, similar to a collective monetary policy. This allows the discovery of the total potential of the land to be done through a gradual and iterative learning process.

Permit Tokens: Permission for development requires buying all necessary Permit Tokens from all neighbors who would be affected, using the landowner’s allocated budget of LandCoin, therefore creating an incentive to propose developments which minimize these impacts and the need to buy Permit Tokens. Permit Tokens would come in many types, each representing a different type of impact, such as overlooking, blocking sunlight and daylight, noise, change of use, etc. They could also be temporary, requiring periodic renewal, to account for evolving impacts of land use decisions.

Permit Price-setting: Each landowner will need to signal their individual preferences over neighboring land use by setting prices for each of their Permit Token types. The prices for all types would add up to a limited total to prevent abuse. For example, if a neighbor highly values direct sunlight in their garden for tomato growing, they may set the price of their ‘Sunlight Permit Token’ as 5 LandCoins for every 10 hours of annual sunlight exposure lost. Once these prices are set, the tokens can be bought without further negotiation. Market conditions, where citizens’ and developers’ preferences meet, shape the character of local development.

Impact calculation: The cost of acquiring the necessary permissions would be determined both by the objective scale of impact, and the subjective preferences of citizens/agents. For example, a development that causes a small amount of overshadowing would require fewer Sunlight Permit Tokens. However, if that land is next to somewhere where sunlight is highly valued, such as a solar farm, even a single Permit Token might become very expensive because of how highly the neighboring landowners value sunlight. This cost would be impact modeled before development, and verified using measured data after the development is built.

Crowdfunding: For certain land uses which are in high demand for the community, such as public amenities, neighbors can donate to these projects the LandCoins they have been allocated or paid so that they can fund all necessary permissions. Quadratic funding-style formulas might be used.

Next horizons

As a pathway for exploring how decentralized civic infrastructure can reimagine how we transact different types of value, land use is currently something that is the centralized responsibility of Taiwan’s local and national governments and therefore serves as an opportunity for experimentation in a sandboxed context.

But this logic can be extended beyond land use regulation. What if all forms of economic value can be transacted through token systems that recognize our economy’s relationship with ecological systems of our bioregion? This could expand the concept of LandCoin into a bioregional currency backed by local ecological potential, where regenerative activities correspond with the issuance of the currency. Similar to how Permit Tokens recognise different types of value on their own terms, a multi-valent bioregional currency may be backed by multiple factors, from the carbon cycle, soil health, biodiversity, water system integrity, air quality, to care, and recognize overlooked value flows. In redesigning a new decentralized civic infrastructure of how we understand and transact value, we may also begin to address the systemic issues that arise out of fiat money untethered from any material, social and ecological constraints, and create new economies based on a more comprehensive understanding of value.

There are strategic entry points into bioregion-rooted economic systems that start with decentralizing other responsibilities of the government. For example, a tax relief scheme can encourage more regenerative activities, by allowing the tax to be paid using a digital currency that is pegged to the health of the bioregion, issued in a decentralized manner through various regenerative activities in accordance with collectively-agreed rules. Similar proposals like this have been made, such as Mata Atlantica Restoration Currency for the restoration of the tropical Atlantic Forest of Brazil.

Use Case 3: Knowledge Provenance for Collective Sense-making

How a democracy functions depends on more than just its decision-making protocols, such as voting. It is also shaped by how its citizenry makes sense of itself and the world around it, through the exchange of information and data, and the construction of a shared understanding of truth. How this knowledge is disseminated and exchanged is critical to shaping how we exercise our agency in a democracy, as it deals not only with the integrity and security of data, but also the information it contains. News media plays a critical role in this knowledge ecosystem.

Having diverse, trustworthy sources of information is crucial in guarding against misinformation and informing how citizens participate in democratic processes. In other jurisdictions, such as the European Union and its Digital Services Act, controlling misinformation still relies on social media providers regulating themselves, resulting in power heavily imbalanced in their favor. This use case explores alternative ways of building trust in the knowledge ecosystem without gatekeepers or favoring the big players, by returning the agency to establish trust back to journalists and their sources, through a decentralized civic infrastructure of knowledge provenance verification. In doing so, this infrastructure would support the critical mission of deepening trust in Taiwanese news among its citizenry and the broader Sinosphere.

Existing practices

Currently, news media operate on a basis of trust in journalistic ethics and standards, such as quoting sources accurately, respecting the confidentiality of ‘off-the-record’ information, and confirming facts with two or more sources. However, the news media is polarized, with trust in news in Taiwan as low as 28%. Furthermore, there is increasing use of information warfare through disinformation from hostile actors. This changing context means trust in journalistic ethics alone may not be enough to ensure a viable knowledge ecosystem.

With the rise of AI-generated images, content authenticity and provenance is already being acknowledged as a critical space for securing the integrity of image-based media. Initiatives such as the Content Authentication Initiative and Starling Lab’s 78 Days are creating provenance tools from the point of capture, to storage and end-user verification. While the end-to-end provenance tools provide additional signals for the content’s authenticity, they have limitations in addressing wider issues just outside the provenance chain, such as how these images are contextualized in the captions and article text.

Taiwan’s legislature is also currently deliberating on the draft Whistleblowers’ Protection Act, which will guarantee certain rights for those making disclosures in both the public and private sectors, to encourage more sharing of information. However, this currently requires the whistleblowers’ identity to be revealed in order to benefit from these protections, placing them in a vulnerable situation.

Decentralized knowledge provenance

The provenance of text-based information cannot be addressed by focusing primarily on technical means, unlike certifying provenance from the moment the image is captured by a camera. Instead of seeking to replace trust in journalistic ethics entirely, web3 technology can be used to augment ethical journalistic practices with a decentralized civic infrastructure of certifications that can be verified by the editorial team and media consumer, and provide them an additional signal of trustworthiness. Web3’s emphasis on cryptography, which ensures decentralization can happen with integrity, offers some possible applications, including:

Zero-knowledge proof of identity using decentralized identity credentials

For anonymous sources, the journalist is responsible for protecting their identity, with the editors and readers relying on the journalist’s judgment on the source’s credibility. As part of a Decentralized Identity system, a zero-knowledge proof procedure can verify certain aspects of the source’s identity that are pertinent to the story and their credibility (without revealing their identities). This can be included with the article and verified by anyone. For example, this can be used to prove a whistleblower is employed at the company they are whistleblowing about, by sharing their ‘current employer’ credential without revealing their name.

‘Proof-of-interview’

This variation of the above can be used to prove that the journalist had met with a source, rather than citing secondary sources. A unique attribution credential can be generated, combining signatures of both the source and the journalist, only through voluntary participation of both parties, which proves that some communication between the source and journalist has taken place. This attribution can also encode metadata (such as date and time) to assure that the communication took place before publication. Subsequent articles can cite this attribution as a secondary source, allowing knowledge to be traceable back to its first report.

Anonymous reporting

Reporters may want to stay anonymous due to sensitive stories. This can be achieved by signing articles with a secure pseudonymous identity that only the journalist controls through their private key, ensuring their pseudonym is not used without permission. Considerations must be made to ensure this is only used in justified circumstances and not to evade journalistic responsibility. In traditional news media, use of anonymity is based on editorial policy. This editorial oversight can also be implemented where the signing of articles with the pseudonymous identity requires multisignature with two private keys, one by the journalist and one by the editorial team, backing the pseudonym with the authority of the news publisher.

Decentralized public record

Similar to Starling Lab’s 78 Days project, where authenticated photographs and their metadata are stored on various decentralized systems and protocols such as Filecoin and IPFS, the immutability and distributed nature of decentralized technology can be used to provide a decentralized record of news stories. This removes the possibility that a singular publisher or journalist can come under censorship pressure to take down their stories.

Wider considerations: building trust in the technology

For these approaches to have an impact, they need to be easy to use, for every stakeholder from the editorial team to the reader, making front end design critical. To convince sources to participate in these certifications, they also need to trust that their privacy will not be compromised and only the credentials they choose are shared and verifiable. Care must be taken to decide what amount of credentials are disclosed such that their identity cannot be inferred and deduced from context.

It is critical for these certifications to be based on open source standards, allowing their integrity and vulnerabilities to be reviewed by anyone, and allow anyone to design interoperable verification tools to work with these standards rather than trusting a single provider. These tools might be first piloted with traditional news media outlets, where they can be built on top of the readership’s existing trust, rather than establishing it from scratch.

Next horizons

While certifying the provenance of journalistic sources goes some way in deepening trust, how we interpret and make sense of that information is also critical. Collaboratively building shared meaning while respecting diversity of opinions is critical to a thriving pluralistic democracy. Systems such as X’s Community Notes (formerly known as Twitter’s Birdwatch) help design a knowledge economy that incentivizes the supply of information that is deemed useful across a range of opinion groups. The Community Notes system recognizes ‘value’ of information as individually subjective, but aggregates these individual preferences in consensus-creating ways. This lends itself to web3 implementation where a similar system can be realized as a decentralized protocol for an information sense-making and rating token system that can be interoperable with different forms of civic infrastructure. For this to be scalable, it will need to address vulnerabilities such as coordinated attacks by hostile actors, such as by interoperating with decentralized identity systems.

Next steps

In light of the multiple crises we are facing, of climate, wealth inequality, and democracy itself, the need to reimagine the underlying infrastructure of our civics is more urgent than ever. To quote the core principles in Dark Matter Lab’s Radicle Civics work, “To address this deep code problem we must even preempt assumptions of a social contract with a state or a government. Civics for us extends far beyond conventional representative democracies, bordered places, and central jurisdictions. Civics starts instead with the most elemental of our social relationships: our mutual interdependencies from which forms of social organization emerge. In this sense, reimagining civics is about both process and outcome.”

We hope to be building these decentralized civic infrastructures in the coming years in Taiwan and beyond, and we invite you to join us in this process. If you are interested in participating, building experiments, or have other ideas and feedback about how we can use web3 technology to transform civics from the bottom up, get in touch with us.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere appreciation to the experts who generously contributed their insights and engaged in meaningful conversations for the development of the paper and these articles. Their expertise and invaluable contributions have played a pivotal role in shaping the essence of this work. We would like to thank (in first name alphabetical order): Arthur Brock, E. Glen Weyl, Jacob Lee, Joon Lynn Goh, Kaliya Young, Mary Camacho, Matt Prewitt, Primavera de Filippi, Scott Moore, and Vitalik Buterin.

We also extend our gratitude to all the individuals who contributed to this paper, both through offering invaluable feedback and actively participating in content creation. Their insights and contributions have been instrumental in shaping this work. We would like to thank (in first name alphabetical order):

Ministry of Digital Affairs: Audrey Tang, Eric Juang, Hao Yuan Ting, Mashbean Huang, Yu Jhen Kuo, and Yue Yin Li.

Dark Matter Labs: Arianna Smaron, Charles Fisher, Eunsoo Lee, Gurden Batra, Hyojeong Lee, Indy Johar, and Shu Yang Lin.

Frontier Foundation: Frank Hu, Lucky Chen, Noah Yeh, Peixing Liao, Vivian Chen, Wei Jen Liu.

Individuals: Gisele Chou, Jeremy Wang, and Jia Wei Cui.