Plural Money: A New Currency Design

Matt Prewitt

February 7, 2022

Money is a bad system for keeping track of whom society owes a favor. The problem is that money is universal, not plural. It therefore undermines communities and impoverishes everyone. Here’s why and how to fix it.

In the first part of this piece I’ll begin by outlining a theory of value that helps to clarify money’s role in society. Then, I’ll explain the idea of a universal unit of account, before wading into the old conversation about voice/exit and specifying how money undermines community.

In the second part, I’ll sketch a proposal for a new system of community currency. This is just a first sketch: it leaves many questions unanswered. But I think it points the way toward a new kind of money that would be more respectful of community and plurality, and may even unlock enormous real wealth across the globe.

I. A Power Theory of Value

Think of money like a cable that plugs into a power bank. There is power out there in society. Money lets you tap in and use some for yourself.

What is power? In their recent book, The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow offer a useful taxonomy. They name three forms of power:

-

Control of violence

-

Control of information

-

Charismatic power

Control of violence is what a warlord has when she possesses more guns than anyone else. It’s also what a property owner has when he can call the police on trespassers, or what corporations have when they can call on courts to enforce their contracts.

Control of information is the power of knowing important things others don’t, from the laws of physics to a bitcoin wallet seed phrase. Google and Facebook know things about us that we don’t, and therefore have power over us that they can sell to advertisers. When the KGB has a mole in the CIA, and the CIA has no mole in the KGB, the KGB has power over the CIA.

Charismatic power is the power to get others to do what you want without recourse to the prior two forms of power. Like the other forms of power, it can be good, bad, or in between. Wise leaders and legitimate governments have it for perfectly good reasons. But demagogues have it for bad reasons. It also sometimes makes sense to put interpersonal privilege in this category – say, the German engineer who gets listened to more than he should because his accent sounds authoritative.

These three forms of power interact seamlessly. For example, information can defeat violence (think of the underdog rebels intercepting the juggernaut empire’s plans). Charisma can defeat information (think of a charming imperial agent seducing a rebel into revealing that the empire’s plans were intercepted). Violence can defeat charisma (think of the imperial agent locked up in the rebels’ prison). Each form of power can defeat each other form of power under the right circumstances.

Money buys all kinds of power: violence, information, and charisma are all for sale at the right price.

Now let’s take a deeper look at exactly how money works.

Money’s Three Faces

Economists teach that money has three functions, not one.

-

First, it is a means of exchange: it lets you confer power to others.

-

Second, it is a store of value: it lets you delay the exercise of power in time.

-

Third, it is a unit of account: it lets you measure many things by a common yardstick.

I view the third function as the most interesting. The first two are important, but they are less unique to money.

Consider a small community in which no one had any concept of money. Exchange could still occur – even without barter – because people could simply do things for one another in circles of mutual aid.[1] (I’d mend Albert’s fence, Albert would babysit Barbara’s children, and Barbara would give me some fish she caught. If anyone freeloaded too much, the community could punish or expel them.) Moreover, value could be stored in durable non-monetary assets, such as land.

But without money, the members of the community wouldn’t be able to talk about the exact or absolute value of things. Chicken farmers would value birdseed, weavers would value yarn, and plumbers wouldn’t have a clear idea of how many balls of yarn a bag of birdseed was worth. Everything would only be evaluated in its close context.

Money lets everything be compared to everything else. It accomplishes this by pinning every particular thing against a relatively universal backdrop: power. And viewing everything in terms of power, in a sort of observer effect, actually changes everything.

Universal Units of Account Enable Capital Exit

The ability to compare things in universal terms opens up the possibility of more exchange between communities instead of just within them. After all, mutual aid economies don’t work well between different communities, because the norms that dissuade freeloaders live within communities. Thus, through its function as a universal unit of account, money lets people accrue value in one community and bring it to another.

It’s good for communities to be able to trade and interact with each other. But universal units of account (which, recall, aren’t the only way to facilitate trade and interaction) have a dark side. They are like a shortcut that doesn’t entail real social integration. People interacting through money are only aligning their evaluations of things in terms of power – they are not integrating their norms of justice, accountability, and legitimacy. In short, their communities are not growing together.

Again, some interaction is better than none, so it’s not exactly a bad thing that money lets distrustful communities trade with each other in this arms-length way. The real danger is that we don’t want this power-based style of interaction, which is appropriate enough between distrustful communities, to displace the mutual-aid interactions within communities. For that would erode the norms of justice, accountability, and legitimacy that make communities what they are.

This is a matter of differentiating between inside and outside. You don’t track mud into the house, or put your bed on the front lawn, or pay your children for their love, or give your employer’s partner a foot massage. Different modes of interaction make sense within and without communities. Money crosses these wires. In so doing, it burns the fabric of communities.

Everybody knows that money can, in some general way, corrupt communities. But I want to be specific about how it happens. Put simply, money makes it easy to uproot power accrued in one community, and transplant it to another. Let’s call this capital exit.

Capital exit is how mud gets tracked into the house; it is how the language we speak with our enemies becomes the language we speak with our friends. When anyone who accrues power within our community can cheaply remove it, we can no longer assume that our community will return what we put into it. This makes us lose faith in the process of mutual aid – the idea that what we give to others will come back to us. And without a commitment to mutual aid, we lose the reason behind our reverence for the norms of justice, accountability and legitimacy that constitute our communities.

This is a devastating value destruction, in every sense of the word value. The trust and norms that prevail within communities unlock uniquely rich and productive forms of cooperation. They are the source of enormous power. Therefore – returning to the idea of observer effect – money as a universal unit of account actually diminishes precisely the community-based power that it purports to measure.

The Trouble With Exitocracy

In 1970 Albert Hirschman popularized the idea that there are two ways for individuals to influence groups: voice and exit. You can work within the system and change it using your voice, or you can threaten to leave, forcing the group to respond.

Today many people are particularly interested in the power of exit.[2] Let’s call them the New Exitocrats. They say: Leave your country if it doesn’t do what you want. Leave the corrupt and rule-bound financial system for the freedom of crypto and DeFi.[3]

Exit is undoubtedly an important check on institutional corruption – Hirschman was right. But the New Exitocrats are performing a bit of sleight of hand. (Though not always intentionally: some of them are surely confused themselves.) Their trick is to conflate personal exit with capital exit.

Without question, people should be able to depart from unjust regimes. The communist and fascist autocracies of the 20th century were horrible in no small part because they prevented emigration. But the right to remove capital from communities is logically different and much more questionable than the right to leave and start a new life.

Traditional money, and indeed traditional private property, has a kind of forgetfulness. It stores no information about where it came from, and in a way, asserts that its provenance is irrelevant. However, this ahistorical quality is a moral fiction. The value of land was always co-created over time by people other than its owners. Profit taken from a business always owes something to the loyalty and sacrifice of customers and employees.

If money (and other forms of private property) had memories, these memories would reveal that ownership and wealth is always co-created and underwritten by a community (or communities). Any economic institution – including a currency – that intends to support the social fabric upon which it depends must respect this fact.

Again, I am not saying anything new. This is the reasoning behind a very old idea: community currencies. It’s clear that keeping wealth within communities could make them healthier and wealthier. Community currencies could in a sense de-universalize the unit of account, enabling more plural notions of value to flourish. But despite lots of rethinking of money, community currency hasn’t, to be frank, gotten much real-world traction.

I think the reason for this is simple. Capital exit has been too cheap. Community currencies like Berkshares are interesting and good, but they don’t profoundly change the world, because they don’t profoundly change how their holders think. People who accrue wealth in community currencies still readily remove it from the community (i.e., they sell it for dollars) because, like most ordinary people in 2021, they still think in the universal terms of the almighty dollar. Or the bitcoin.[4]

In order to really preserve community, money needs to have a higher exit cost.

II. A New Protocol For Community Currency

Blockchains are curious things.

Bitcoin maximalism is more or less a campaign to amplify exitocracy. It envisions an even more universal unit of account than the dollar, and an international system of asset ownership even less accountable to community norms than the international capitalism we already have. In a bitcoin maximalist world, democratic processes would have zero ability to influence the monetary policy behind the hegemonic unit of account. This is less than the small amount they have today through national politics.

On the other hand, blockchain-based cryptocurrencies do something traditional money can’t: in the form of a ledger, they keep a paper trail showing their history. This paper trail isn’t of much use if it consists only of anonymous, throwaway cryptographic addresses: without more information, the ledger can’t locate money’s provenance in a community. But, combine the paper trail with proof-of-personhood identity, smart contracts, and a few more clever ideas – and we can see the prerequisites for a genuinely new and much better kind of money. Here’s a rough sketch of what it might look like.

I should also say before diving in that this is a light and loose design. Many aspects of it, especially the transfer taxes, require more engineering and experimentation before we can be confident that they efficiently solve the problems they intend to. But we know that the status quo isn’t working very well and our trajectory is troubling. And we have new tools at our disposal that our predecessors lacked. Whatever you think of this design, history certainly does not show that it fails. And the stakes could hardly be higher: Community, prosperity, democracy, the environment, freedom and self-determination. So I feel a moral imperative to experiment with things like this.

A Network of Communities

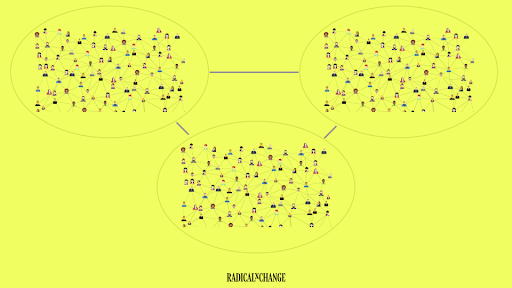

First, imagine a network of communities[5] on a network like Ethereum.

The communities we need to picture are in relation to each other, not isolation. Membership rolls could overlap; people could be members of many simultaneously. Communities could organize around different principles, ranging from geography to religion to shared hobbies. They could differ from each other radically.

Beneath this diversity, the communities would operate internal currencies using a basic common protocol. This protocol’s shared features are not covert universalization: they let the communities recognize and mutually support their shared commitment to plural value systems.

I’ll now outline major design features, with more detail in the subsequent sections.

-

Communities would keep track of who their members are, using a shared proof-of-personhood identity system. This could consist of one or several anti-sybil networks like Proof of Humanity, BrightID, or Goldfinch’s UID. Members’ real-world identities need not be made public, or even known to the community, but there must be a way for people to prove or disprove their association with multiple communities – even anonymously, or with zero-knowledge proofs.

-

Communities would keep track of the internal governance power held by each of their members. For example, if a community used simple voting, all members would have equal governance power (i.e., 1/n, where n is the number of members). If they governed themselves using a quadratic voting based system like RadicalxChange Voice, they would track each member’s share of the community’s overall “voice credits”.

-

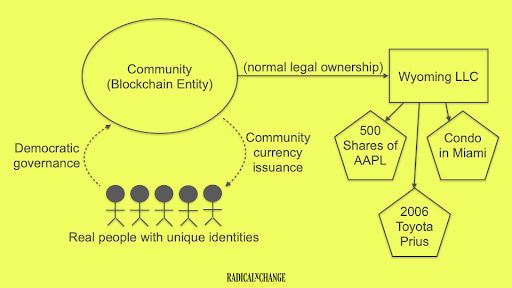

Communities would legally possess real-world assets on behalf of their members. For example, each community might own (in addition to things like NFTs and other digital assets) a Wyoming LLC, which would act as the community’s practical legal owner of off-chain assets, such as land. Community decisions about commercial interactions with other currency communities, and/or the external world, such as buying or selling assets, would be taken democratically.

-

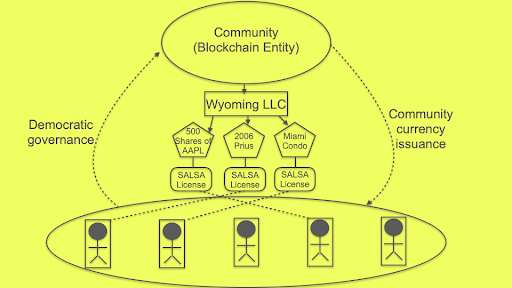

Communities would each issue a special sort of community currency. Members would need this currency to personally possess any community assets.

-

This is not like normal money. It can’t be used for just anything. The main thing you can buy with it is, speaking precisely, self-assessed licenses (i.e., SALSA or Harberger licenses) for the possession of community assets. SALSA (“self-assessed licenses sold at auction”) is a form of partial common ownership. More on this in the next section.

-

Transfers of the currency other than for SALSA licenses, including transfers between community members, are “taxed” at varying rates, with higher rates for transfers outside the community. The revenues from transfer taxes go into the community treasury. From there, the community can decide democratically how to use its wealth to purchase more community assets, and/or redistribute currency to members.

-

Those are the basic protocol elements that all the communities would need to have in place to have economic relations with one another – that is, to send their currencies to one another. But beyond that, the pluralistic possibilities are endless. Some communities might decide to fund common goods using QF; others might do something else. Communities could experiment with different internal democratic decision structures, and other matters large and small.

Having clarified that, for the remainder of this piece I will specify the basic shared protocol in more detail.

How These Communities Own and Use Assets

To recap:

-

These blockchain-based currency communities own assets in the real world.

-

Their members obtain possessory interests in community assets using a system of partial common ownership (SALSA licenses).

-

The members steer the overall community democratically (e.g. using RxC Voice or some other thoughtful democratic system).

To make it concrete, picture a community that has five members, and owns three different assets: a car, an office building, and some shares in a publicly traded company. Here’s how that would look:

The different members of the community would use their community currency to purchase rights to use the community’s stuff. For example, Annie might buy the SALSA license to the Miami condo for a year. In that time she could do whatever she wanted with it, except sell[6] or destroy it: she could, for example, renovate it, or live in it, or even lease it out to a non-community-member in exchange for dollars. At the end of her time holding the SALSA license, the new winning bidder would pay the winning bid to her (not to the community) in community currency, and she’d hand over the SALSA license.

Here’s an illustration:

Specifics on SALSA Licenses

SALSA licenses are a fairer and more efficient form of ownership than traditional private property. They’re inspired by a roughly Georgist point of view. To dive into the philosophy and economic logic, see here, here, and here. For now, let’s just specify the mechanics.

When a community member buys the SALSA license for an asset, she gets the right to use or improve that asset as she pleases for a certain period of time.[7] It’s a bit like a lease. However, unlike a lease, she must also pay a special license fee to the community treasury, which is calculated as a percentage of the price paid at auction. This is a bit like a property tax. And at the end of her license period, the license goes back up for auction. She can continue to hold the asset by putting in a winning bid. If she does not win the bidding, then the winning bidder’s payment goes to her, and she relinquishes the license.

For different sorts of assets, the license durations and the fee rates should be different. In their democratic process, the community would need to set these parameters (as well as a few others, such as when SALSA licenses may be combined or subdivided).

As I mentioned above, the money from fees on SALSA licenses may be used by the community to purchase more assets, or may be distributed to the community members individually, as dividends.

SALSA holders may use their assets freely. They have an incentive to maintain and invest in them, because when the assets go back up for auction, the new SALSA price goes into their pocket. They may use SALSA assets to obtain outside currencies or assets – e.g., renting them out for dollars. However, SALSA holders may not unilaterally sell their assets, because they’re not permanent owners. Permanent dispositions and purchases must be approved by the community as a whole.

How the Community Currency Works

Each community issues its own community currency (CC). Decisions about money supply, such as whether to issue more CC, are made democratically.

But the CC cannot be used for just anything. It is primarily used for purchasing SALSA licenses.

The CC is the only currency accepted in SALSA auctions and for SALSA fees. This is easy to ensure because the auctions for the SALSA licenses and the payments of SALSA fees could all happen on-chain, enabling the special status of the CC to be hard-coded.

The hard question is what else we need to do to minimize the amount of wealth that bleeds out of the community through the CC. This is tricky because on the one hand, we want the CC to facilitate commerce between community members; on the other hand, we don’t want people using the CC to buy removable assets from other community members, like dollars or shares of stock. That would make capital exit too cheap and easy.

In short, outside of the SALSA license transactions, we want all CC transactions to be strongly biased towards (a) transactions between community members for (b) services that can’t be directly removed from the community, not goods that can. Let’s take (a) and (b) in order.

Specifics on Taxing Exit

The CC generally cannot be sent from one address to another without a tax being calculated and sent into the community treasury. Here are the details of those exit taxes.

-

CC transfers to any unknown, unverified addresses are simply blocked. CC can only be sent to an address verified either by the issuing community, or a different but mutually-recognized community using the currency protocol. All such peer communities would reference shared proof-of-personhood networks to stop sybils; so anonymity and privacy are possible, yet every possible recipient of the CC is a real person with known links to known communities, who is verifiably not operating multiple identities.

-

Second, CC transfers to non-community members are taxed quadratically, in the following way. The amount of wealth a transferor has, not the amount they’re transferring out, determines their quadratic exit tax rate. Suppose someone has 100 units of CC wealth (combined CC and SALSA assets). The square root of 100 is 10. 10 thus becomes the number by which any removal is divided. So, if a person with 100 CC wealth wishes to transfer 2 units of CC to a non-member of the community, it will cost them 20. The other 18 will go into the community treasury.

-

The logic here is that the more wealth a person has within a community, the greater their obligations to the community, and the greater the cost to the community when they remove it.

-

This steep exit tax is mitigated if you are transferring from one community to a member of a second community that has substantially overlapping membership. Thus, if community A and community B have 75% identical membership, then all else being equal, only 25% of a transfer from a member of A to a member of B is taxed like an external transfer.

-

-

Intra-community transfers are not always free either – they are only generally free between people whose membership profiles are identical.

-

Recall that each community tracks the amount of governance power each member has. Now suppose person A has 1/5th of the governance power in community X, and 1/100th of the governance power in community Y. Governance power is weighted by the amount of power over other people it implies.[8] So if there are 5 people in community X, and 200 people in community Y, this means person A has twice as much governance power in community Y as in community X. Thus, A’s profile is “1/3 community X membership, and 2/3 community Y membership”.

-

Say person B is only a member of community X. When she transfers community X’s CC to person A, only 1/3 of the transfer – i.e., the amount of overlap in A and B’s membership profiles – is exempt from the quadratic tax. The remaining, taxed amount (2/3 of the transfer) is reduced further by the amount of overall overlap between communities X and Y per bullet #2 above. So, extending this example: if X and Y’s memberships overlap 50%, then only 1/3 of person B’s transfer to person A is subject to the quadratic tax (50% group overlap * 2/3 personal overlap).

-

Encouraging Transactions For Services, Not Goods

There is one way that members of the same community can make free transfers to one another, even though their membership profiles don’t perfectly overlap: they can document personal services performed in exchange. If B performs a personal service for A, and A either attests to it (if de minimis) or documents it (above a certain value level), then the transfer is free.

This is not a perfect solution, but I suspect it is a manageable stopgap on a dangerous loophole.

Personal services do not provide the same easy path to capital exit from the community as goods. To be sure, if A wanted to take capital out of the community, she could hire B to perform services resulting in the creation of some durable product, which A could then sell outside of the community. But at least this would create a market for service provision by community members. Simply letting A buy goods from B would make it too easy and cheap to remove wealth and would put extrinsically wealthy community members on different footing from the others, since they could accrue CC simply by selling goods (or outside currency) to other members.

Still, again, this is a weakness in the system, and communities will need to intelligently and scrupulously police it. For example, transactions in “services” whose price is really a rent on capital, like high-priced investment advice, shouldn’t count as personal services. We’d need to develop a kind of jurisprudence around this, and likely a whistleblower reward to aid enforcement.

It might sound a little complicated, but in truth, communities solve harder problems every day.

Reflections on Stability

In a way, this design creates a parallel economy of interacting communities. To succeed, it must be stable. It must not wither into insignificance relative to the regular economy; or be successfully attacked by outsiders who will inevitably try to undermine it.

Here’s why I think it might succeed.

-

SALSA is a more efficient form of asset management than traditional ownership. Over time, these communities would thus manage capital better than the outside world, and get wealthier relative to it.

-

Intact communities are in and of themselves a huge source of wealth. Because these communities would be resistant to capital exit, mutual aid could flourish in them. They could therefore become pillars of the well-being of their members, seeing this, non-members of communities would be inspired to join existing communities or form new ones.

-

Attacking this system would be expensive. Malicious parties trying to buy into communities all at once – instead of working in, by developing relationships with many different members, or gradually gaining voice in their democratic structures – would involve paying huge transfer/exit taxes, which would enrich whatever communities you’re trying to weaken.

-

There is no single point of failure. This is a network of diverse communities who interact with each other on the minimal condition that they all operate exit-resistant currencies. In the spirit of decentralization, it would be hard to take down the whole thing.

Maybe best of all, this system doesn’t fight against existing structures of human community and relation. Instead, it offers them a shield against entropy, helping them survive and grow.

III. Conclusion

Money has been bulldozing plurality for centuries. What if we could stop it?

In this system of plural money, what amounts to a network of mutual aid societies would arise. Individuals would accrue wealth not globally, but in a meaningful local context. Richer economic relationships would develop, shielded from the Midas-like touch and Medusa-like gaze of a universal unit of account.

Power derives from community. So money, which tries to measure power, should rigorously respect community, and strive to leave it intact. If it did, it would unlock not only a more moral and diverse world, but by any reasonable definition, a wealthier one.

Also, this isn’t crazy. The legal, technical, and intellectual ingredients for a system like this exist today, and didn’t just a few years ago. Let’s try it!

This piece owes its existence to many amazing conversations with amazing people. I will name only a few: Glen Weyl, Alex Randaccio, Divya Siddarth, Paula Berman, Audrey Tang, Jen Morone, Vitalik Buterin, Graven Prest, Joel Rogers, Andrew Kortina, Paul Healy, Jack Henderson, Nelson Del Rio, Steven McKie, Andrew Trask, Jo Guldi, Daniel Chen, Kevin Owocki, Daniel Schmachtenberger, Kaliya Young, Jürgen Braungardt, Gil Steinlauf, Ben Pitt, David Chiba, Rossella Dacomo. Thank you!

Notes

David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years ↩︎

Balaji Srinivasan is one of the most well-known New Exitocrats. He is not alone: his view is shared by many if not most Silicon Valley elites. ↩︎

Technology seems to make exit easier and more powerful. Voice, on the other hand – participation through democracy, through internal institutional means – remains as clunky as it was hundreds of years ago. Maybe clunkier, since now we’re all living in bewildered filter bubbles. I don’t think this is inevitable. I think that technology can strengthen voice, just as it has strengthened exit. But when technology is fused with capitalism, technology biased towards exit is what gets built. It’s just easier to make money tearing the social fabric than sewing it. ↩︎

The only exceptions to this have been cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrencies have managed to install a new unit of account into some of their holders’ minds – but only while their value is still being actively speculated upward. In other words: only when there is an exit cost. ↩︎

Call these communities DAOs if you insist, but aside from the fact that we’re imagining this built on top of Ethereum’s base layer, there isn’t much that’s truly “decentralized” about these organizations. And I’m not sure why the word “autonomous” applies, since they’re governed democratically. ↩︎

Annie might decide it was a good idea to sell the condo outside the community, for dollars or bitcoins. She could then propose that idea to the community, and maybe get a commission from the community for handling the sale. But the dollars or bitcoins obtained for the condo would go to the community treasury. ↩︎

Lots of prior writing, including mine, has described SALSA licenses as continuously on the auction block. Here though, I want to describe them as auctioned periodically, so that each time you buy one, you get a lease-like interest that lasts for some known period of time. In my experience, this simply makes SALSA easier to understand for many people, and raises fewer questions about planning and investment. I still think that for many kinds of assets, it makes sense to auction SALSA licenses very frequently or continuously. Some communities might decide to make their SALSA auctioning more “continuous” than others. SALSA NFTs that could easily facilitate these transactions already exist. ↩︎

We may also want to weight governance power by the amount of wealth per capita a community holds in dollar or bitcoin terms. This weighting would make it possible to join and participate in “trivial” communities that only hold a little wealth – say, the birdwatching or lawn bowling societies – without paying too much of a cost in terms of your ability to interact seamlessly with members of your more economically significant communities. ↩︎