Plural Money, Socially-Provided Goods, and the Principal-Agent Problem

Matt Prewitt, E. Glen Weyl

September 8, 2022

The problem with using money for socially-provided goods; and the problem with not using it

Money is an economic lubricant: it helps goods and services slip and slide toward where they can be used more efficiently. Without lubricant, things get “stuck”. They don’t go where they’re needed most, and value is wasted.

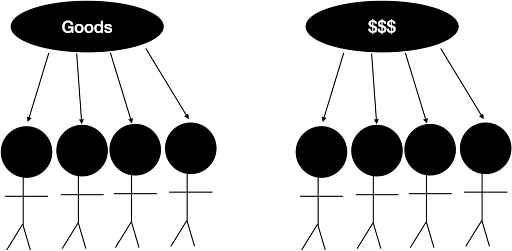

Yet, sometimes using money backfires, causing goods to be distributed less efficiently. Consider public education. Giving citizens cash, instead of schools, would less efficiently achieve the important public objective of education. Individuals might, for example, misspend the money, or fail to coordinate around supporting efficient, broadly shared institutions. The same logic holds for roads, telecommunications, and other socially-provided goods that support broadly shared goals.

The obvious inefficiency of charging money for these things leads many to conclude instead that a perfectly egalitarian distribution of benefits would be optimal, or better. In many cases, that’s surely true. But just as clearly, it isn’t always. After all, some people and places need access to education, roads, or telecommunications much more than others. Poor people need certain things more than rich people. Rural people need some things more than urban people. Etc.

If the government addresses these differences by technocratically deciding who needs what, it risks huge mistakes. Even if it avoids mistakes, it makes itself dangerously powerful. And now we’re back to money and markets: this is why they can sometimes be helpful. They aggregate information about where good education and roads are most hotly needed – without directly concentrating power in the government.

In short, distributions of goods by decree, or by market, are inefficient and worrisome in different ways.

| When it’s inefficient | Unwanted consequences, even when efficient | |

|---|---|---|

| Distribute goods by decree | When we don’t know the best way of allocating benefits | Makes the government really powerful |

| Distribute goods through a market, i.e., using money | When we don’t want to further empower the rich and/or encourage people to seek money | Empowering whoever can print money |

The problem with using money for private goods; and the problem with not using it

Above, I described the problem from the point of view of governments distributing benefits – should they use decrees or markets? But a near-perfect analog of this problem exists with private actors. It is the principal-agent problem.

Think of it this way. Companies often have a clear goal in mind, such as selling a product. To succeed, they need the help of salespeople. And those salespeople need resources – computers, cars, digital subscriptions, airplane tickets, educational materials, and more.

The company thus has a choice: how to get the salespeople the things they need?

It could leave it to the market, telling salespeople to buy whatever they need with their own money. This would have the advantage of letting the salespeople apply their own intelligence to the complex problem of how to support their work. However, it would also put less rich salespeople at a disadvantage, and encourage all salespeople to skimp on expenses, thus under-resourcing their work.

Another option is for the company to buy the things salespeople need and distribute them equally. This puts all the salespeople on equal footing, and ensures that they have the basic tools to succeed – a good thing. However, the company might also be wasting money, because it cannot guess as well as the salespeople themselves what they need to succeed. Salespeople all work in different ways and in changing contexts: some might benefit more from education, others from better relationship management software, others from more travel, etc.

Navigating between these options, most companies have arrived at a familiar intermediate solution: They give salespeople finite budgets to expend, with limited discretion, on work-related goods and services. This lets them apply their own judgment to the problems they face without letting them cash out those budgets for non-work purposes.

But notice that the salespeoples’ receipts must be reviewed to check the relationship between the expenditures and the sales work. Thus, a new inefficiency shows up in this solution: the price of auditing. This arises whenever principals entrust agents with real money, because money can be spent on anything, from sales calls to fancy socks to gardening equipment.

Companies could save themselves an auditing burden if they were able to issue money that could only be spent on appropriate expenses. What would this look like? Here, let’s pivot back to the context of socially-provided goods like education and housing and look at how market designers have thought about this dilemma.

The problem with vouchers

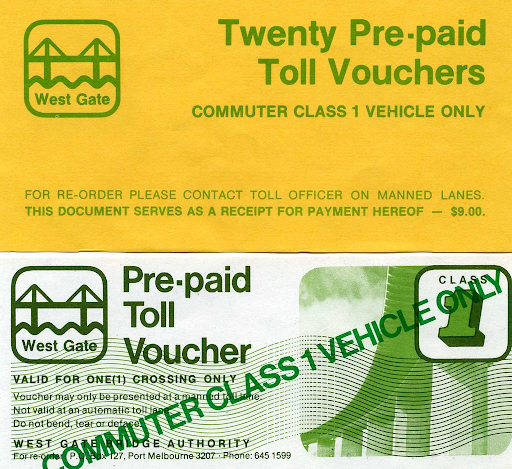

Market designers like Nobel Laureate Al Roth have made a career of looking for ways of getting the best of both worlds between markets and decrees. One of the market designer’s favorite tools is the voucher. Using vouchers, the government can make an equal distribution of a special currency, only usable only for some particular set of goods. People can then use that to apply market-like intelligence to the allocation of socially-provided goods – paying great teachers more, for example, or deciding which roads are most important to improve.

The equal starting distribution of the currency means that it isn’t biased toward the interests of the already-wealthy, and the restricted utility of the vouchers ensures that they get spent on the intended goods.

This latter feature also solves the issue we noticed in the case of companies forwarding money to their agents. Neither governments nor companies would need to audit receipts if they could issue vouchers that were only spendable in pre-approved places.

So far so good. But traditional vouchers, too, have a limitation: They force everyone to spend roughly the same amount on the set of goods they’re usable for. This undermines part of the point of having a market, because people don’t get to decide how much to spend on the goods in question. Yet if you try to address that by letting people buy and sell the vouchers, you reintroduce all the problems of a normal market, like empowering the rich, and opening the door to resource misuse. And if you try to address it by decreeing who gets more vouchers, you unduly empower the issuer, and risk getting things badly wrong.

This is a very old dilemma. Excitingly, there are promising new ways of weaving through it.

Lotteries and plural money

Take the example of government housing. Suppose the housing authority issues everyone a voucher, good for renting one bare-bones apartment, for a year. To some people, this will be very valuable. But others won’t have any desire or need for it.

Instead of making the latter group wastefully spend their vouchers, or letting them sell it for cash (defeating the point of voucher), let them enter a special sort of lottery. They can take, say, a 75% risk of losing their one voucher in exchange for a 25% (or less) chance of winning four vouchers – enough for a very fancy apartment. Public profits from the lottery are recycled back into the system so that each single voucher goes a bit farther.

Vouchers can be extended further by incorporating other features of markets which may not undermine context-specific and/or egalitarian goals. For example, individuals could be allowed to save vouchers and earn interest on them, allowing those who do not need housing now to save up for a more attractive unit later. Another example is allowing some exchanges of value into adjacent contexts. For example, society may have an interest in equally supporting the welfare of citizens, but may not know which combination of health, education and housing each citizen needs. Or, a society may support informational access for citizens, but not know which combination of media (print, broadcast, social) is most useful. Vouchers that can be used in a market across these adjacent contexts, but not beyond them, might allow for this additional flexibility while maintaining the public egalitarian purpose.

This opens up new avenues for issuing local, egalitarian, purpose-limited currencies to help with the allocation of socially-provided goods. These special currencies could help manage access to everything from public sports facilities to carpool lanes and even schools.

Even more excitingly, local currencies could go beyond those traditionally public cases, becoming accepted by certain local vendors, and opening up to limited forms of exchange with other, similar new local currencies. In some early writings, we’ve started to explore what this pluralistic system of money might look like.

Non-government issuers, too, could create special currencies. Companies could use them to replace loyalty point systems, gift certificates, and the like. They could even obviate expense auditing: Working with networks of partners, they could programmatically “white-list” certain expenditures, building alliances of companies whose employees patronize one another.

Community-based currencies have never delivered on their promise in the past because it is simply too easy and too tempting to exchange them for dollars. Such “cashouts” poke a hole in the balloon that local currencies are trying to fill, resulting in a kind of context collapse. Crucially, we can deal with that challenge now, programming digital currencies to work like vouchers with thoughtful, self-enforcing rules about what they can be used for. This will make community currencies more than just currencies: they’ll be scaffolding for local development, encouraging people to look to do business locally before trying to extract money.

Because the rules and contours for these new currencies are customizable, they can even do subtler things than just supporting local trade. For example, an underlying reason to support local trade might be to support small, proprietor-operated businesses. So instead of mechanistically drawing lines around the city to define “local trade”, we might extend the currency to work at small proprietor-operated businesses in adjacent municipalities; or exclude their use at national chains. For the first time ever, we could construct disincentives for removing the currency from communities (i.e., the “cashout” problem), and rewards for keeping it in. The possibilities are thus endless. If communities could control and govern their own currencies this way, they would have a powerful new tool to build economies that better reflect their values, distribute goods among themselves more fairly, and lay the foundations of more mutualistic economies.

Municipalities are in an ideal position to kickstart experiments like this. After identifying one or several socially-provided goods whose distribution they’d like to improve, they can issue special currencies of this kind to all their residents. Blockchain technology can help (1) manage the currencies without requiring users to do anything more than interact with a simple website or app; while also (2) allowing for customizability in terms of the vendors that accept them; and (3) self-enforcing limits on transmitting the currency to businesses or people outside the community.

This could begin a historic shift from centralized to decentralized money, and a new era for local currency. We owe it to ourselves to start experimenting.

Thanks to Aksel Sterri for helpful comments.