Synthetic Subjects

Matt Prewitt

December 20, 2022

The cry of a baby can doubtless be described in purely organic terms, but the wail becomes a noun or verb only by its consequences in the responsive behavior of others.

–John Dewey, The Public and its Problems, Ch. 1

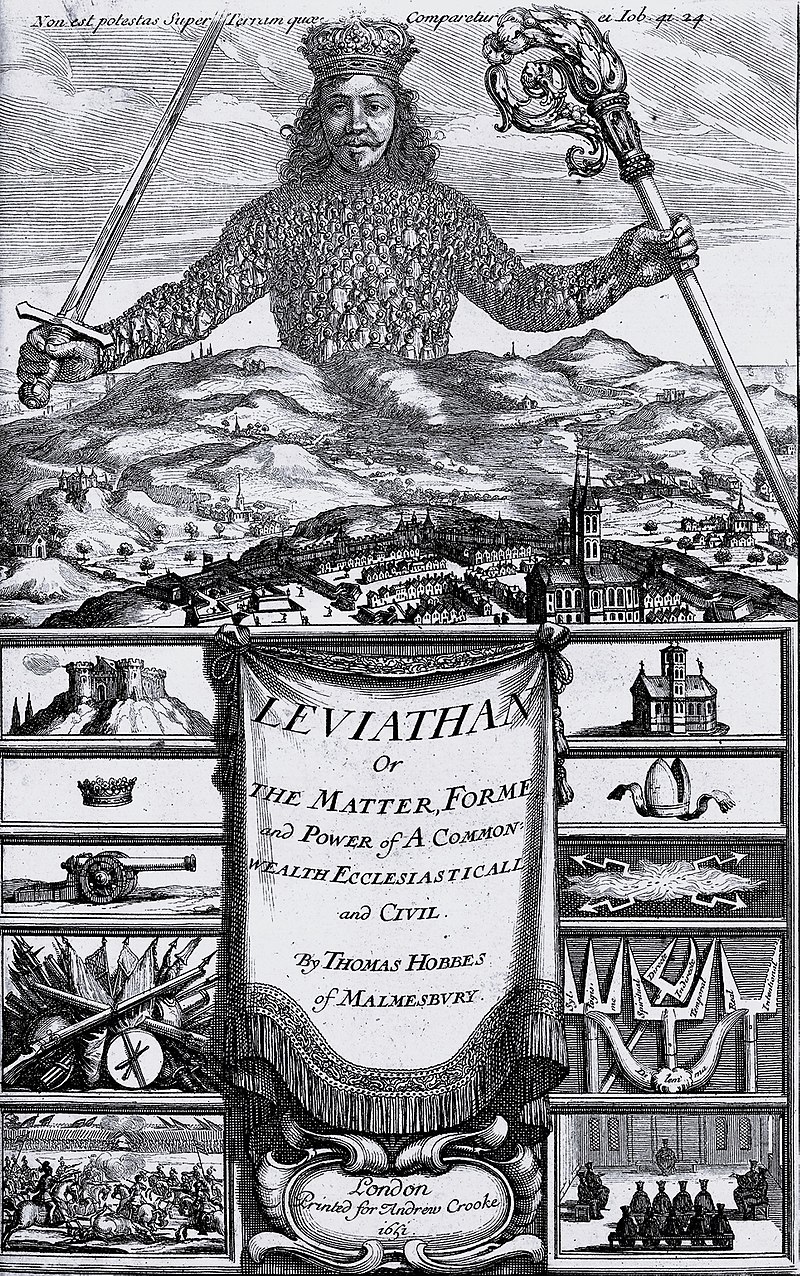

I am not a huge fan of Thomas Hobbes’ thinking, but I love his cover art.

Hobbes worked with an engraver named Abraham Bosse to produce this memorable image, the upper part of which depicts a colossal king composed of his subjects. Bosse seems to have drawn from a peculiar tradition of portraiture represented by the 16th-century Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo, in which the subject is depicted as a composite of other things:

For Hobbes, the composite king illustrated how he saw the power of the sovereign as a focused combination of the power of the people.

I am fascinated by the notion of subjects and subject-like entities – institutions, authorities, communities – emerging from smaller units, or being discerned within or among them. It resonates with the idea of bodies as associations of cells, and many other natural phenomena. Unlike Hobbes though, I do not see any necessary connection between this sort of thing and authoritarian politics. I do not observe land-bestriding sovereigns dominating the political or the natural world, and I wouldn’t want to. Instead, I see something more complex: living, pulsating ecosystems of quasi-Leviathans, large and small, democratic and authoritarian, living and dying, good and evil, overlapping, merging, and individuating.[1] None are static or closed. All are changing and incomplete, with “a crack where the light gets in”, as Leonard Cohen put it.

I call these entities synthetic subjects. This is an abstract concept that wraps around many others. It reveals deep overlaps between apparently disparate fields like law, economics, ethics, language, computing, and more, showing them to be different angles on the same thing.

I’ll begin this discussion by commenting on the difference between my worldview and Hobbes’. I’ll then give a definition of synthetic subjects. Finally, I’ll touch on several topics that I think the idea helps illuminate. If it doesn’t help us understand the world, there’s no reason to carry it around.

Is There A Baby In Hobbes’ Bathwater?

Hobbes thinks that everyone should, for their own good, submit to the absolute authority of a sovereign. He says this resolves internal conflict, and thus strengthens communities against their enemies:

The only way to erect such a Common Power, as may be able to defend [people] from the invasion of Forraigners, and the injuries of one another, and thereby to secure them in such sort, as that by their owne industrie, and by the fruites of the Earth, they may nourish themselves and live contentedly; is, to conferre all their power and strength upon one Man, or upon one Assembly of men, that may reduce all their Wills, by plurality of voices, unto one Will . . . . [T]he Multitude so united in one Person, is called a COMMON-WEALTH, in latine CIVITAS. This is the Generation of that great LEVIATHAN, or rather (to speake more reverently) of that Mortall God, to which wee owe under the Immortall God, our peace and defence. For by this Authoritie, given him by every particular man in the Common-Wealth, he hath the use of so much Power and Strength conferred on him, that by terror thereof, he is inabled to forme the wills of them all, to Peace at home, and mutuall ayd against their enemies abroad.

Hobbes has to be taken seriously. From a certain angle his argument for the concentration of power – if we don’t do it, someone else will, and they will just crush us, so we should do it – is inexorably true. But before plunging headlong into Hobbesian authoritarianism we must ask why the whole political and natural world isn’t already so organized.

Why don’t ecosystems like coral reefs and forests look like Hobbesian dictatorships? Why does messy competition seem to help economies do better, not worse? Yes, ultra-concentrations of power sometimes seem to strengthen countries, as happened in 17th-century France, early imperial Rome, etc. And it seems to work for private companies. But plenty of other times, power concentration seems to make countries brittle or foolish, as in 20th century dictatorships from the Nazis to the Communists to the Baath, and the countless incompetent monarchs of past centuries. Likewise, don’t forget that while private companies get a lot done, they also collapse with far greater regularity and spectacularness than countries or ecosystems can afford to.

This variety is satisfyingly explained by the hypothesis that Hobbes’ top priorities – strengthening internal order and external defense – are not the only important things happening in complex societies. If they were, these priorities would steamroll much of what makes societies (and ecosystems and economies) rich, resilient, and beautiful. Indeed, however much you value order, it is simply not reasonable to want the kind of order Hobbes advocates unless certain other conditions exist. These conditions ground claims that authority is justified, or legitimate. These conditions happen to be the sorts of things that non-authoritarian non-Hobbesians – you know, democrats, egalitarians, and other softies – are rather interested in.

Legitimate Authority Arises In Coherent, Just Communities

Suppose that we selected an arbitrary group of people with no meaningful connection, like all those whose birthday happens to fall on the 11th day of any month. Does it make sense for this group to submit to an Absolute Monarch Of Eleventh Day People, in order to secure order amongst themselves and strengthen their hand against people with other birthdays? No. Worse than being absurd, it would destroy society, which, I think you’ll agree, depends on unhindered cooperation between people of diverse birth dates.

Or think of a group that includes a violent internal caste system, such as the population of 20th century South Africa, or early modern India. The ties linking people in these societies are not merely random, like birthdays. Still – should everyone in such societies submit to a single sovereign? No – the oppressed classes might reasonably be less worried about foreign enemies than local oppressors. They would lack good reasons to delegate their power to a sovereign that wasn’t going to liberate them from these oppressive relationships.

Many contemporary Hobbesians – that is, people who think that the public authority ought to be organized more hierarchically, as it is in corporations – seem blind to this set of questions. This essay explores what they overlook, taking Hobbes’ notion of a “Leviathan” and reimagining it with an integral dimension of legitimacy. When should institutions’ claims to authority be taken seriously, and when not? As suggested above, I’ll argue that they should be taken only as seriously as the communities from which they arise. Where those communities are incoherent, like the birthday community, or unjust like apartheid South Africa, the idea of a legitimate authority is nonsense. So too, is the idea of a synthetic subject.

The idea also saves a baby from Hobbes’ bathwater. It offers (small d) democrats, who sometimes shy from the harder questions about authority, a palatable way of understanding where authority comes from, and when it is justified and real.

Naming Means Caring

Consider your pet dog. Now consider a wild stray dog. Among other differences, your pet is much likelier to have a name.

I’d argue that the act of naming reflects an awareness of obligation. You accept that your pet dog’s fate depends on you. The reverse holds as well – if your dog is neglected, your fate is to be a bad dog owner. In the act of naming, you accept this special relationship.

You don’t name a lab rat.

Something like naming also occurs with objects, places, and crucially, social institutions. A serious relationship with another person — a friendship, a professional partnership, a romance — acquires a sort of entityhood. In a marriage, the marriage itself needs to be nurtured and respected in order to thrive. This is not exactly the same thing as nurturing the other person, which becomes clear when marriages are dissolved in order to prioritize the interests of both partners. Similar dynamics occur in a company, a community, etc.

Synthetic subjects, then, are special relational structures. They’re the ones we name. Naming them means accepting that they have interests of their own, and that their interests are our interests.

What Does This Have To Do With Technology?

Marshall MacLuhan argued that the content of any particular medium like print or television is less important than the medium itself – “the medium is the message”. The upshot: “Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot. For the ‘content’ of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.”

Similarly, what is being said is less important than the synthetic subject saying it. Synthetic subjects are not just deeply entwined with means of communication: they are means of communication, like the airwaves through which our messages to one another travel. We understand each other through the symbols of our nations, tribes, and digital spaces. And when we stop communicating by those means, the corresponding synthetic subjects – nation, tribe, or online platform – disappear.

The meaning-laden words that make us who we are — words like democracy, justice, and freedom, which Dworkin called interpretive concepts — are defined in communities. Communities are defined by their roughly-shared understandings of such words. Through linguistic processes, communities define themselves and negotiate a shared understanding of their high ideals.

And fascinatingly, our synthetic subjects speak back to us. “Germany” has a certain rough understanding of “democracy” that Germans hear and understand. Beyond words and concepts, legal institutions speak to us in sometimes rough terms. The voice of our community would go silent, in a certain way, without the tax bill, the contract, and the notice of lawsuit.

So it is with technological media. The printing press, radio, film, television, mobile phone, world wide web, web3, and so on – all gave rise to new kinds of societies and political communities. They are the raw material of synthetic subjects. MacLuhan was right. Our communication channels themselves matter more – and in fact say more about us – than whatever we are using them to hear, say, or do.

Numbers Versus Words

Much has been written on whether computers can be sentient. In some ways, this seems to depend on whether there is a fundamental difference between how computers and humans process information. If there isn’t, then it’s hard to see why computers couldn’t eventually “be conscious” in the same way that people are. But there is at least one simple difference. Computers prefer information formatted as numbers, while humans prefer it in words.

Humans are clumsy with numbers, and computers are clumsy with words. To deal with words, computers must first translate them into ones and zeroes. It took them decades to acquire the impressive capacities of linguistic manipulation they now possess; and they could not have achieved this without massive rote copying of human language patterns. Conversely, the best mathematicians on Earth flail through basic arithmetic operations like fish learning to walk, while simple calculators, dating back to the abacus, have completed them with ease.

What’s the difference between numbers and words? Numbers have exact and unchanging definitions; words do not.[2] Dictionary entries must be tweaked every few years — they are dynamic and approximate snapshots, rooted in a place, time, and context — while mathematical definitions such as 4 = 2 + 2 are eternal and exact.

Wittgenstein called this feature of language “unsharpness”. Unsharpness is a big part of why computers struggle with language. Programmers can’t simply “tell computers what words mean.” That is why computer systems like GPT that use words logically and grammatically require the help of vast amounts of statistical information concerning humans’ word usages. Word meanings cannot be reduced to logical or definitional rules.

Yet, the instability and imprecision of words’ definitions is still not the essential point. For this is symptomatic of a deeper fact: words are partly constituted by the way subjects (i.e., people) interpret and use them. It is not words that are changing and indefinite, it’s us. Numbers do not work this way because their definitions do not depend at all on what anyone thinks. They are open to study, but closed to interpretation.

Interpretation is a crucial concept for our argument because it connects to the idea of authority. When we use words we typically enjoy, as a matter of social grace, a limited invitation to participate in the process of defining them. For example, if I say “breakfast just isn’t breakfast without a cup of coffee,” you might affirm my sentiment, or disagree. But you will not pull out a dictionary, look up “breakfast”, and tell me I’m incorrect on the basis of what it says there. This is because, if you understand the social game being played, you will permit me to exercise a small degree of authority in defining the idea of “breakfast” through personal interpretation. You need not adopt my interpretation, but if you deny my standing to offer it – my partial sovereignty over “breakfast” – you deny part of my subjecthood.[3] You treat me as a non-interlocutor, just as you would treat a computer. Frankly, it’s sort of rude.

And it isn’t very smart either. You might have the world’s most sophisticated definition of breakfast. But if you think breakfast is completely invulnerable to my interpretation of it, then you really don’t understand breakfast, because you don’t understand what language is. In MacLuhan’s terms, you misunderstand the medium, and a fortiori the message.

Hearing And Respecting Synthetic Subjects

We invite other human subjects to interpret words, and their interpretations matter to us. If we did not do this, we would not be able to commune-icate, that is, to use language to understand one another as subjects, and thus develop a shared social context.

Into this very social context, we invite synthetic subjects. Similar to other human subjects, we take synthetic subjects to have their own interests, and grant importance to those interests. We care what words mean not only to our neighbors, but also to our nations and our gods.

Picture the Oracle of Delphi asking the gods what they ordain; or an earnest judge asking what the law demands; or a CEO pondering what’s right for her company. It does not much matter that these three people would tell different stories about the ontological status of the synthetic subjects they’re consulting. In all three cases they are treating synthetic subjects as actually having interests worth taking seriously.

Some people see only naive credulousness here: the gods aren’t real, the law is made up, the company is just a bunch of shareholders. Deflating synthetic subjects is a form of reductionism which sometimes helps us see the world more clearly, like when the synthetic subject is a wicked myth, or a shared delusion – think of “The German People” for Nazism, or “The Party” for Soviet communists. However, puncturing synthetic subjects is not always enlightening. Sometimes taking synthetic subjects seriously is a prerequisite to understanding how other people see things. For example, even if you don’t take “the law” or “the company” seriously, it’s unquestionable that some people do, like earnest judges and dutiful corporate leaders. And without extending a little credence to synthetic subjects, you will never be able to understand how those people think. And deflating synthetic subjects sometimes destroys valuable social bonds. Suppose I sit down at the dinner table with my loving partner and happy children, and declare that “the family” as such has no meaning to me: it is only the sum of many self-interested individual actions, nothing more. Seeing things this way, let alone expressing it, does much more harm than good. It weakens the sense of mutual obligation and common purpose in the family. Even if it is partly true, the ways in which it is false are much more interesting and important. It is monstrous reductionism.

Everyone takes some synthetic subjects seriously. And when they do, those synthetic subjects become interlocutors. Just as we grant other people some authority in questions like “what is breakfast?”, we give our polities and our families some authority in questions like “what is democracy?”, and “what does it mean to be a good father?”. In this way, synthetic subjects process questions posed in language, returning answers with actual meaning. Sometimes they do this through human mouthpieces – that is, people playing special roles for the synthetic subjects, like judges, spouses, or Oracles of Delphi. In other cases they impress themselves directly on our thinking.

This is how synthetic subjects speak to us. For our computers to perform this feat, no amount of technical development is either sufficient or necessary. The only thing we’d have to do would be to open our eyes, ears, and hearts to them – as we do to other people, animals, institutions, and so on – when we attribute to them the quality of dignity. We cannot prove that other minds exist, or don’t. There is no empirical inquiry here that further information will resolve. There is only a moral one: should we extend our recognition?

Exceeding The Sum Of Parts

Jim Rutt has said that the difference between something complicated and complex is whether we can take it apart and put it back together. For example, if we disassembled an entire Boeing 747, we could put it back together piece by piece and fly it again. But we cannot do that with a human body – or a country, economy, or corporation.

So-called “complexity” is a typical characteristic of synthetic subjects. They have synergies between their components that we can’t completely describe. This is part of the reason that we anthropomorphize them, and listen to what they have to say. We can’t understand them in reductionist terms.

Moreover, complexity makes synthetic subjects extremely economically important. They are the wellspring of economic growth because they are worth more than the sum of their parts.

Economists accept that most economic growth comes from “increasing returns” phenomena – that is, phenomena where value emerges which exceeds the sum of its inputs. Yet, economists struggle to explain increasing returns. They are difficult to reconcile with one of the discipline’s foundational assumptions that most economic activity occurs under conditions of “decreasing returns”, i.e., scarcity and resource constraints.

Economists typically resolve this apparent contradiction by waving their hands toward technology and efficiency as the explanations for the excess value. This is good enough to help them avoid intellectual embarrassment, but synthetic subjects offer a deeper explanation. Just as organisms are what makes some collections of cells more than mere collections of cells, synthetic subjects link atomized, resource-constrained economic processes into integrated “wholes” that are worth more than the sum of their parts. The functioning of synthetic subjects can look from the outside like simply better technology and efficiency. But there’s more to it. A richer conception of synthetic subjects would help economists learn to recognize those important exceptions to their rules, where “better technology” and “more efficiency” can destroy value instead of creating it.

An Attempt At A Definition

Getting to brass tacks, here are what I take to be the main features of a synthetic subject. Each feature requires further explanation, but the overall concept comes into view best when these features are understood together. In no particular order:

-

Synthetic subjects are social processes – projects, ideals, concepts, words. You might also call them “intersubjective” processes.

-

Synthetic subjects have their own interests. Or if you prefer: thinking of synthetic subjects as having their own interests is an efficient mental shortcut to a deeper understanding of the individual interests that comprise them.[4]

-

Synthetic subjects help us process information, but as interlocutors rather than rote transcribers.

-

The information they process is partly indeterminate, incomplete, and susceptible to interpretation. This information is therefore linguistic, rather than mathematical.

-

Synthetic subjects are more than the sum of their parts. They are comprised of not-fully-understood relationships between other subjects. This means they are complex, as opposed to complicated; we are not capable of taking them apart and putting them back together without destroying them.

-

Synthetic subjects govern networks and mediate relationships. In this regard, whatever authority they hold can be legitimate or illegitimate – good or bad, liberating or oppressing, mutualistic or parasitic. I plan to elaborate elsewhere on how ideas about legitimacy from legal philosophy can help us draw this distinction in a rigorous way that applies across many types of synthetic subjects.

-

The inquiry into a synthetic subject’s legitimacy tracks the inquiry into whether it helps other subjects (like us) communicate. Good synthetic subjects constitute a shared context against which richer, more efficient communication may occur.

Conclusion

Synthetic subjects are social processes through which we cooperate, communicate, and understand the world. They are institutions, languages, media, and more. These kinds of phenomena are more than just connective tissue – they take on an entityhood of their own.

There’s much more to develop here, as I suggest in the final points of the definition. I plan on writing more about when we should acknowledge synthetic subjects – when we should accept them as dignified wholes (as nationalists do with states and committed parents do with families); and when we should instead reductively dismiss them. I believe this is a useful framing of an important moral question connected to dignity, politics, and more.

Hobbes is wrong that we should always want Leviathans; polycentric coral reefs are in many ways more attractive. Yet you can’t dismiss every Leviathan you see. A human being, for example, is a kind of Leviathan from the point of view of its cells. Strong communities can, at times, look a little bit Leviathan-like. We need to be careful not to treat these things with too much skepticism and dissembling; while also keeping our guard up against robots, corporations, oppressive social arrangements, and other unworthy claimants on our sympathy. I hope I can offer some useful heuristics for these questions.

–

Thanks to Jack Henderson, Divya Siddarth, Paula Berman, Alex Randaccio, Glen Weyl, and Rossella Dacomo for helpful feedback and conversations.

Notes

This requires qualification. In one way, the natural world is not made of sovereigns. A coral reef, for example, is a domain of plural interpenetrating spheres: the anemone with the parrotfish with the eel with the lobster. But in another way, one does find sovereign-like things throughout the natural world: organisms. An organism looks a bit like a monarch over its cells, which may be sacrificed for the whole. Does that undermine my argument? No. This merits longer analysis, but it will suffice for now to observe that (a) organisms never have absolute authority because they share it with other organisms and much more; and (b) cells are actually not sacrificed for the whole at all costs because there is a degree of pain – i.e., cell death and trauma – beyond which most organisms choose not to live. ↩︎

Philosophers John Searle and Hubert Dreyfus wrote about this in the 1960s and 1970s, while criticizing how A.I. scientists were then thinking about computer cognition. ↩︎

On the other hand, if I assert that breakfast isn’t really breakfast without a dry martini, you might be more dismissive. My authority over “breakfast” does not extend that far; it must remain in dialogue with social practice. ↩︎

From an external point of view synthetic subjects can be described mereologically: they are coherent things or integral wholes. From an internal point of view, synthetic subjects are experienced phenomenologically: they constitute experience. ↩︎